Come Here This Instant!

The precarious life of an “undesirable foreigner” taking refuge in a hostile land

Let us examine for a moment the life in May 1940 of a foreign female refugee in France from an “undesirable” nation.

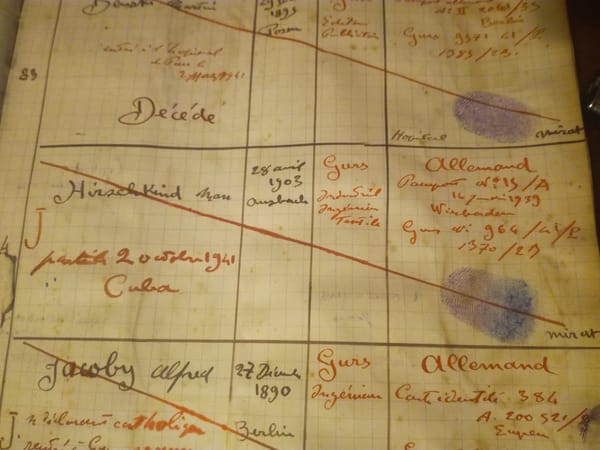

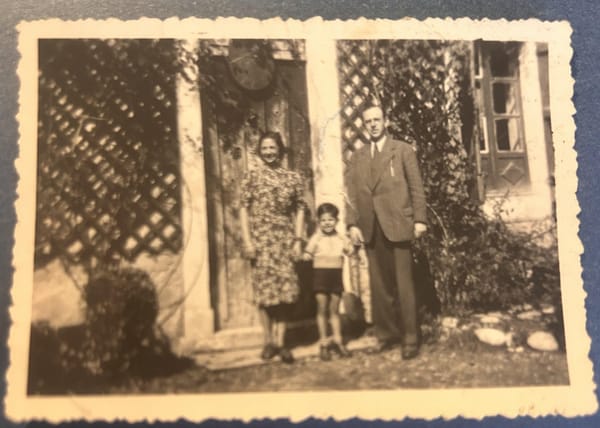

It concerns my father’s first wife, Hildegard, who along with their sickly 4-year-old son Walter, was hoping to reunite with her husband, lately arrested by the Belgian police and sent to France as a preliminary step to being deported to Auschwitz.

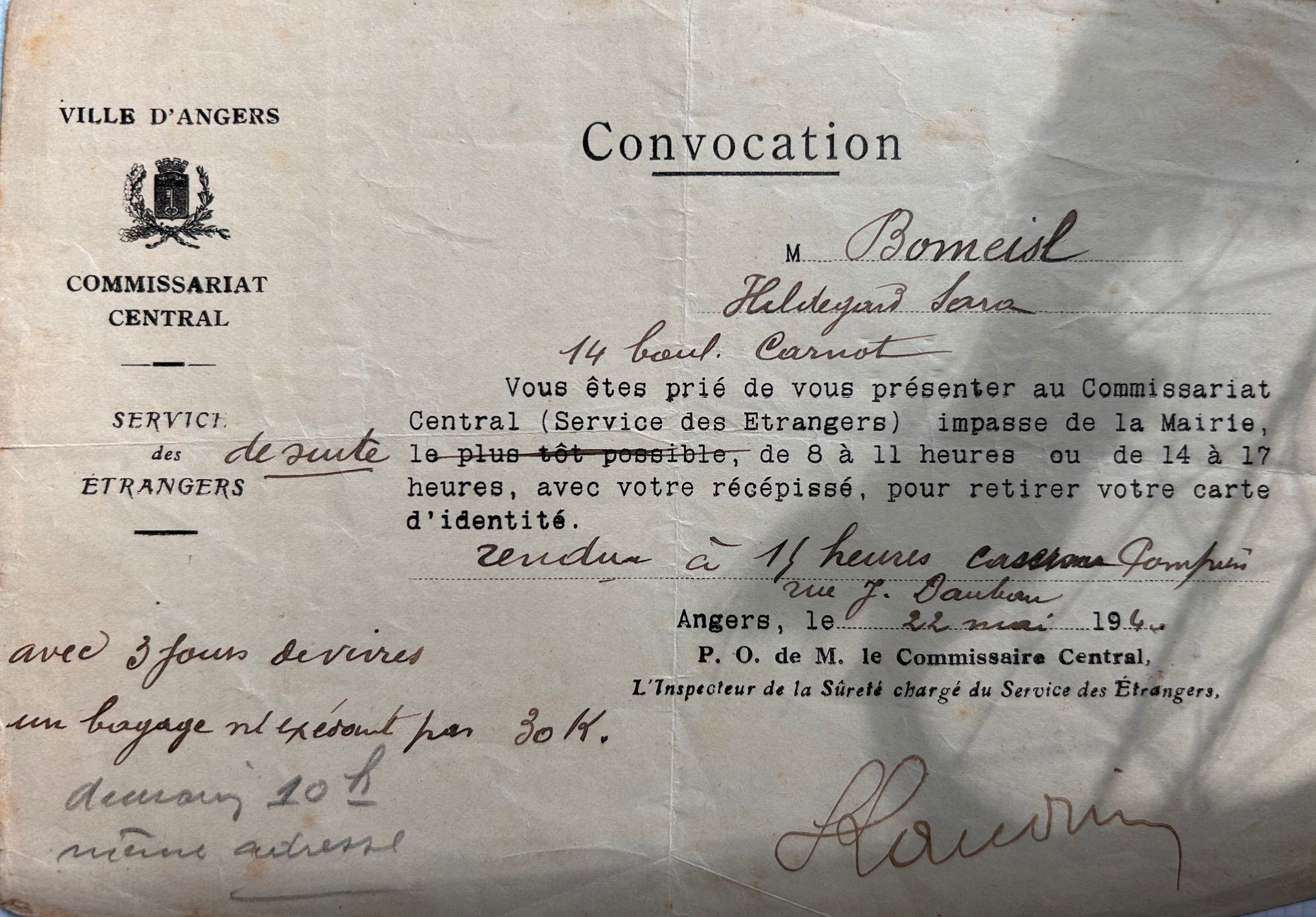

The document was a summons issued by the office of the Angers police headquarters that dealt with foreigners, addressed to Hildegard Sara Bomeisl*. It instructs her to appear this instant before the department dealing with foreigners, at the police headquarters located at town hall road, during the hours of 8 to 11 am, or from 2 to 5 pm. It instructs her to bring her receipt so that she can take possession of an ID card.

*While other paperwork issued by the French referred to Hilde by her married name, Hirschkind, here they refer to her by her maiden name of Bomeisl. Hilde had come to France from Belgium, and the French authorities were doubtless using Belgian-issued papers to establish her identity. It’s unclear whether using her maiden name was a way of degrading her, in addition to naming her Sara, or was merely a clerical mistake. (According to German law, all female Jews had to add the name Sara, and all male Jews had to add the name Israel. So I would have been Michael Israel Hickins.)

Note that the words “as soon as possible” [i.e., appear as soon as possible] are crossed out, and replaced by the line “this instant [de suite, or literally, immediately upon receipt of this document].”

Below this, in handwriting, it says “arrived 11 am at the fire station on rue Jules Dauban May 22, 1940.”

Bring your own damn food

In the margin on the left, it instructs her to arrive with 3 days’ worth of food and no more than 30 kilos (about 66 pounds) of luggage. In pencil is added the instruction, “tomorrow 10 am, same address.”

It is signed by the security officer responsible for the department dealing with foreigners.

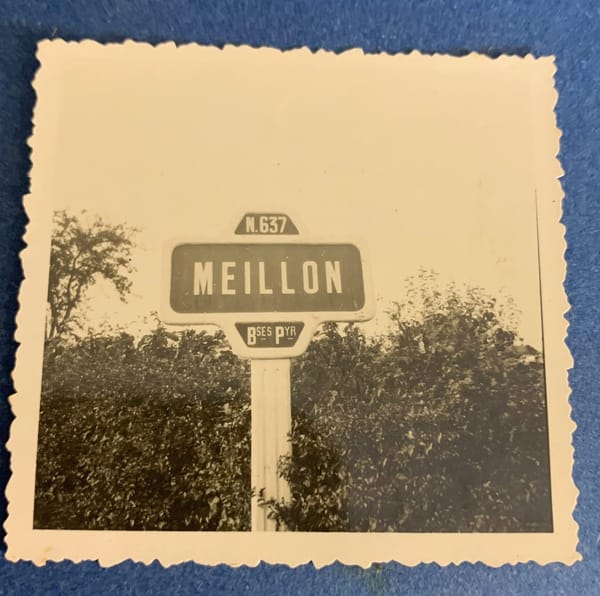

My father Max had been sent to the internment camp at Saint Cyprien earlier that month. Hilde arrived in Angers, hoping to find Max. Far from being reunited with her husband, having been identified as an “undesirable foreigner,” she was sent by the authorities to a different camp some 400 winding, treacherous kilometers (240 miles) away.

The parallels between her life and those of a Latino refugee in the United States, or a Palestinian in Gaza, or a Syrian in Italy, are obvious. People aren’t responsible for the actions of their stated representatives, elected or not. They are only responsible – and we are responsible – for how we treat others.

Do not stand by your neighbor’s blood

As Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg notes, the Jewish sage Maimonides in the 12th century opined that “there is no commandment as great as redeeming captives, for a captive is among the hungry, thirsty, naked, and is in mortal danger… And, "Do not stand by your neighbor’s blood."

Let’s remember these words the next time some godbother tries to use religious texts as a cudgel for the oppression of others.

There are no others – there is only us.