Cuba Libre in Marseille

The United States wouldn’t have him – my parents said it was because of Walter’s tuberculosis, and maybe that was true, maybe the timing of their US visa application or the mandatory health exam was bad, but maybe it was because the US was notoriously stingy with visas for Jews fleeing Nazi Germany – but Cuba had no such qualms.

I've written about this in my memoir, The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family's True Holocaust Story.

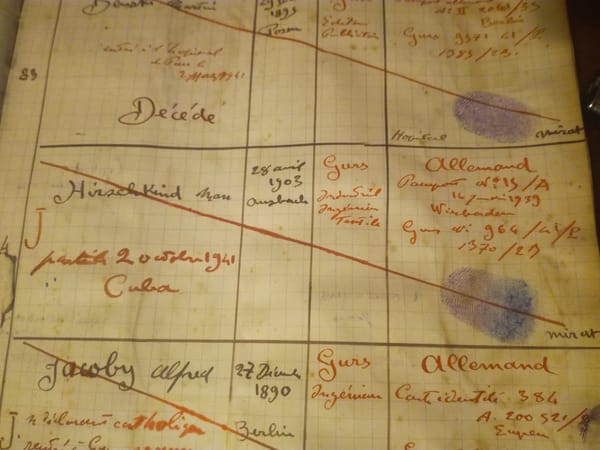

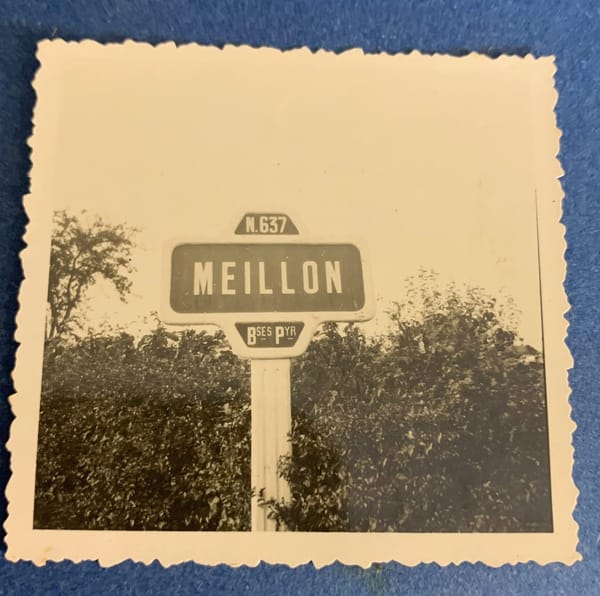

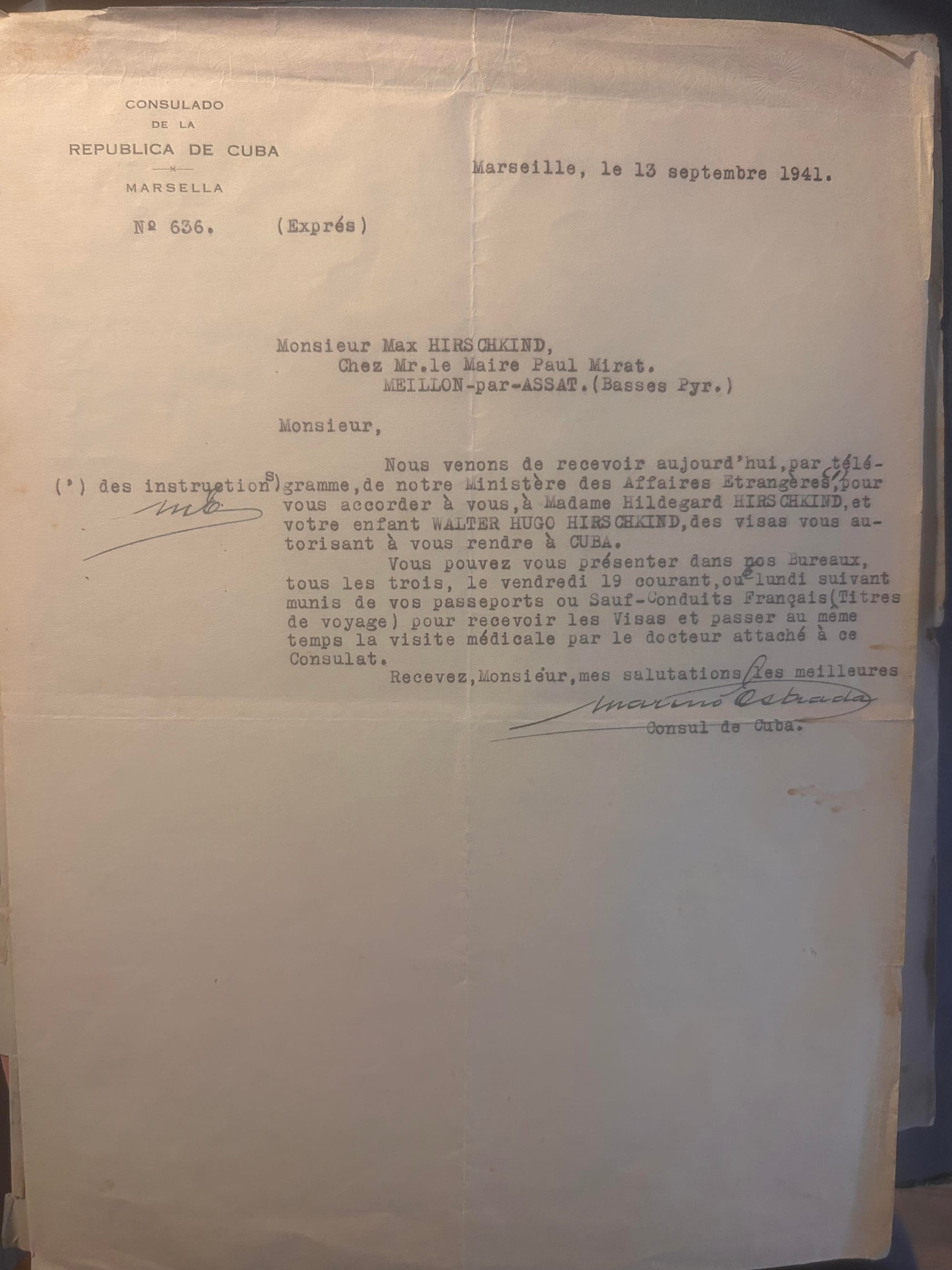

The letter from the Cuban embassy in Marseille dated September 13, 1941, is addressed to my father care of Mayor Paul Mirat in Meillon, in the Basses Pyrenees region.

It says:

“Dear Sir, we have today received a telegram from our Ministry of Foreign Affairs granting visas to you and your wife Hildegard Hirschkind and your child Walter Hugo Hirschkind, authorizing you to travel to Cuba.

“The three of you may come to our office either on Friday the 19th of the present month, or else the following Monday, in possession of your passports or French safe-passage documents (travel authorizations) in order to receive your visas and, on the same occasion, undergo a physical exam performed by the doctor retained by the Consulate.”

It is signed by the consul, Marino Estrada.

The letter was mailed on a Saturday by express mail, underlining the urgency of the matter. No one knew when a given prisoner’s time would run out of the hourglass, the result of arbitrary forces accountable to no one.

If haste were not made, it was entirely possible that conditions would change, that travel permits would be revoked, that people would be separated. Such is the nature of authoritarian regimes: the fantasy of streamlined efficiency is quickly overcome by the reality of arbitrary and corrupt abuse of power by one group over all others.

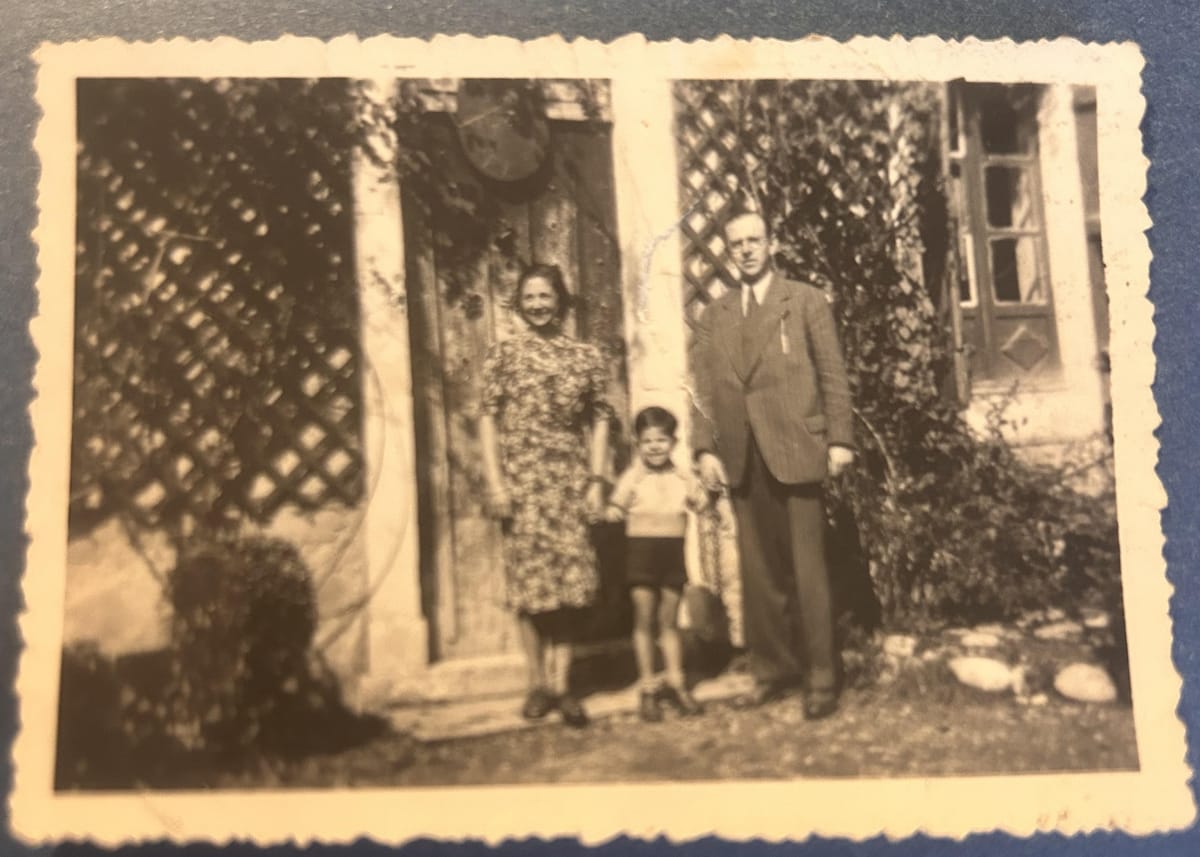

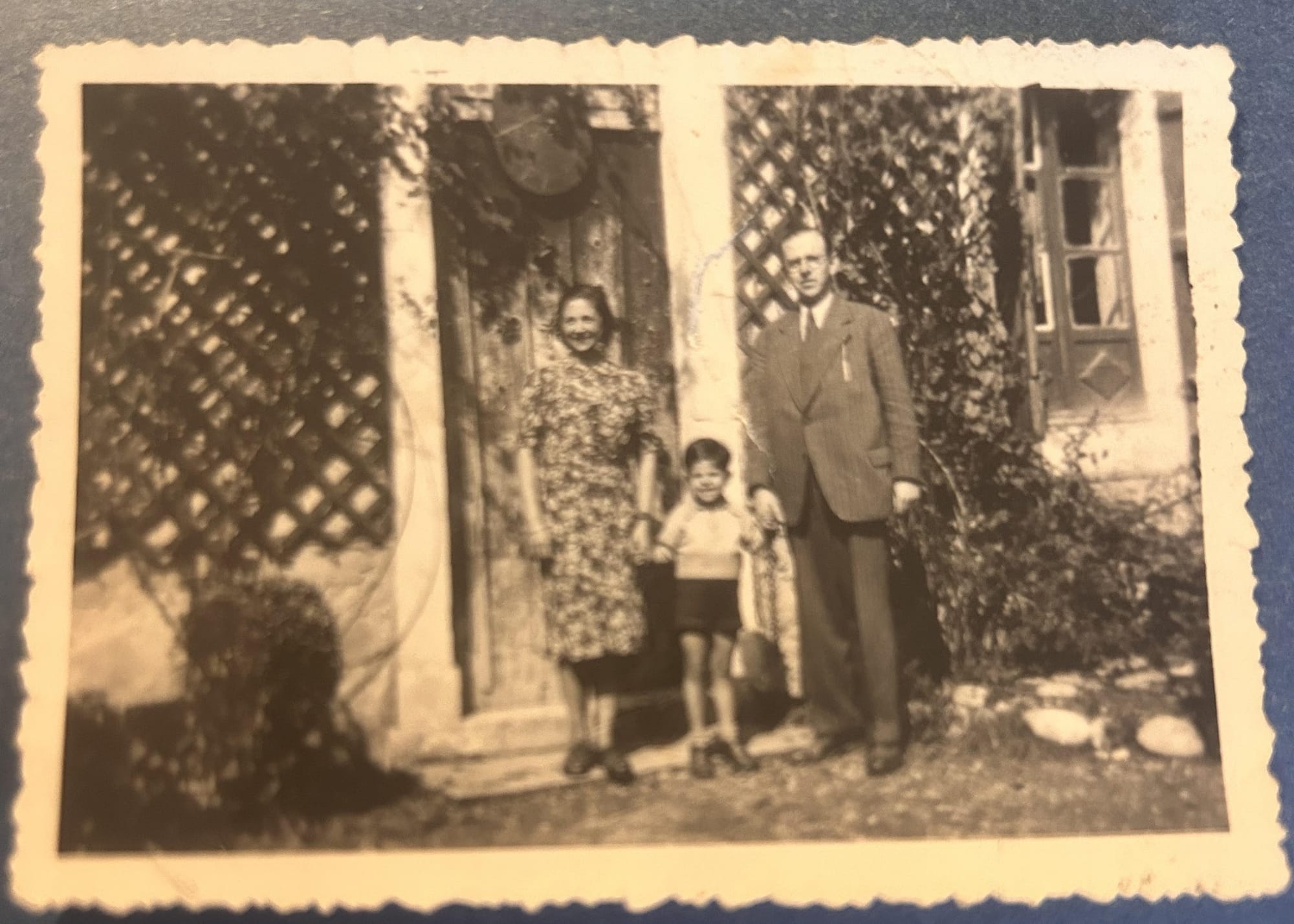

The photo below shows my father, Hilde, and Walter in Meillon, in front of the small house in the garden behind the big house where Paul Mirat lived, probably days or even hours before their departure, on October 27, 1941. Their affects are oddly divergent: my father looks somber, almost absent – as if already thinking about the next stage of their perilous journey – while Hilde looks quietly happy, maybe thankful to be getting the hell out of a place that didn’t really want her and to be going somewhere that was more welcoming. And Walter has an exaggerated grin on his face, almost a grimace; he’s either trying to please the adults who told him to smile, or he’s masking his fear.

Both adults are done up very nicely, my father in a natty suit and tie, with a starched white collar, while his wife is wearing a festive dress – oddly out of season, though. And Walter too, in his shorts and light shirt, seems dressed more for July than October weather. And indeed, the weather was unusually mild in early October 1941, but by the end of the month, it had become unusually cold and there was even snow across many regions of France, including around Pau.

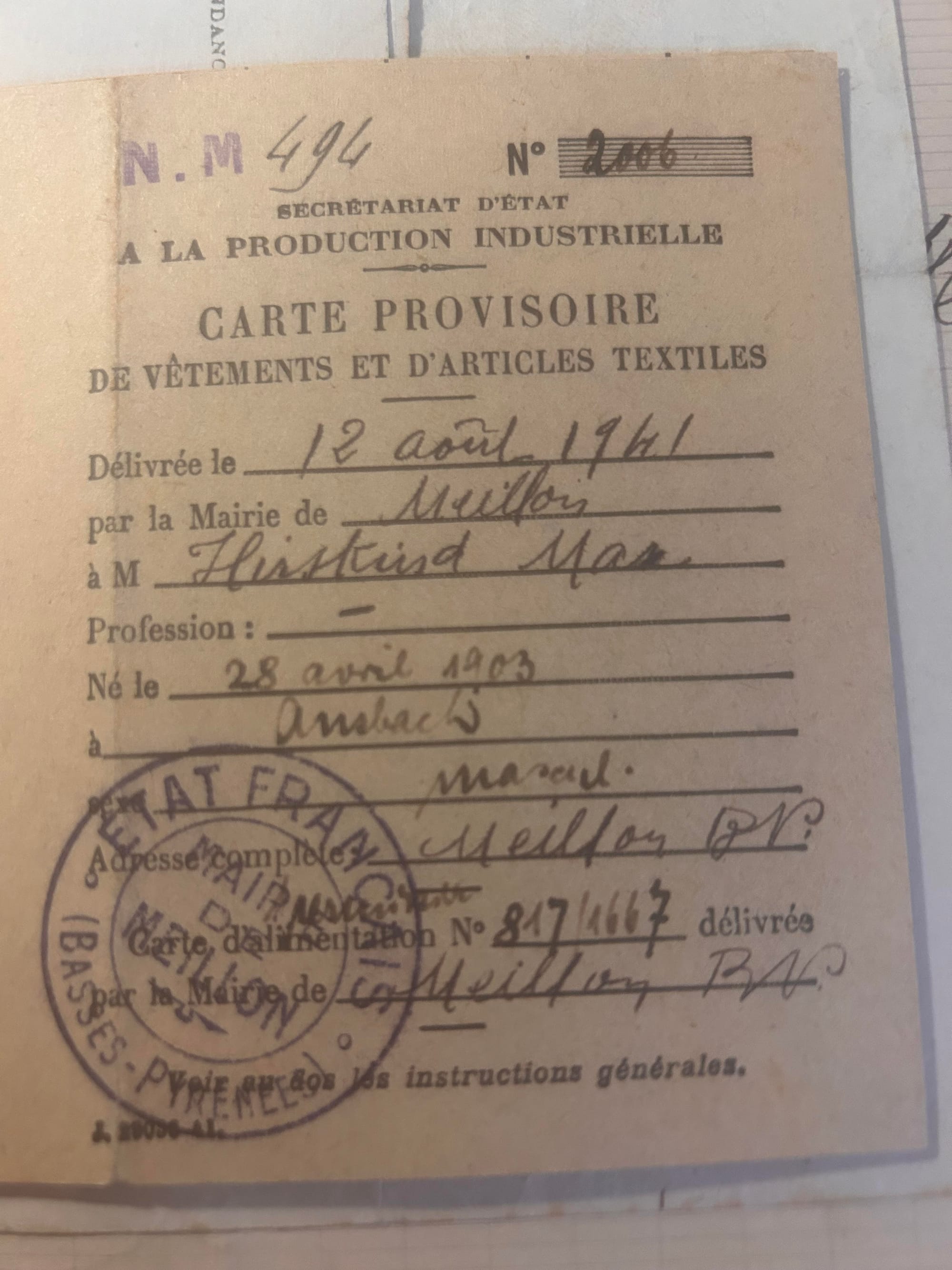

One can imagine that they didn’t have much choice when it came to clothes, although it seems that my father never made use of the ration book for clothing that he was issued while in Meillon.

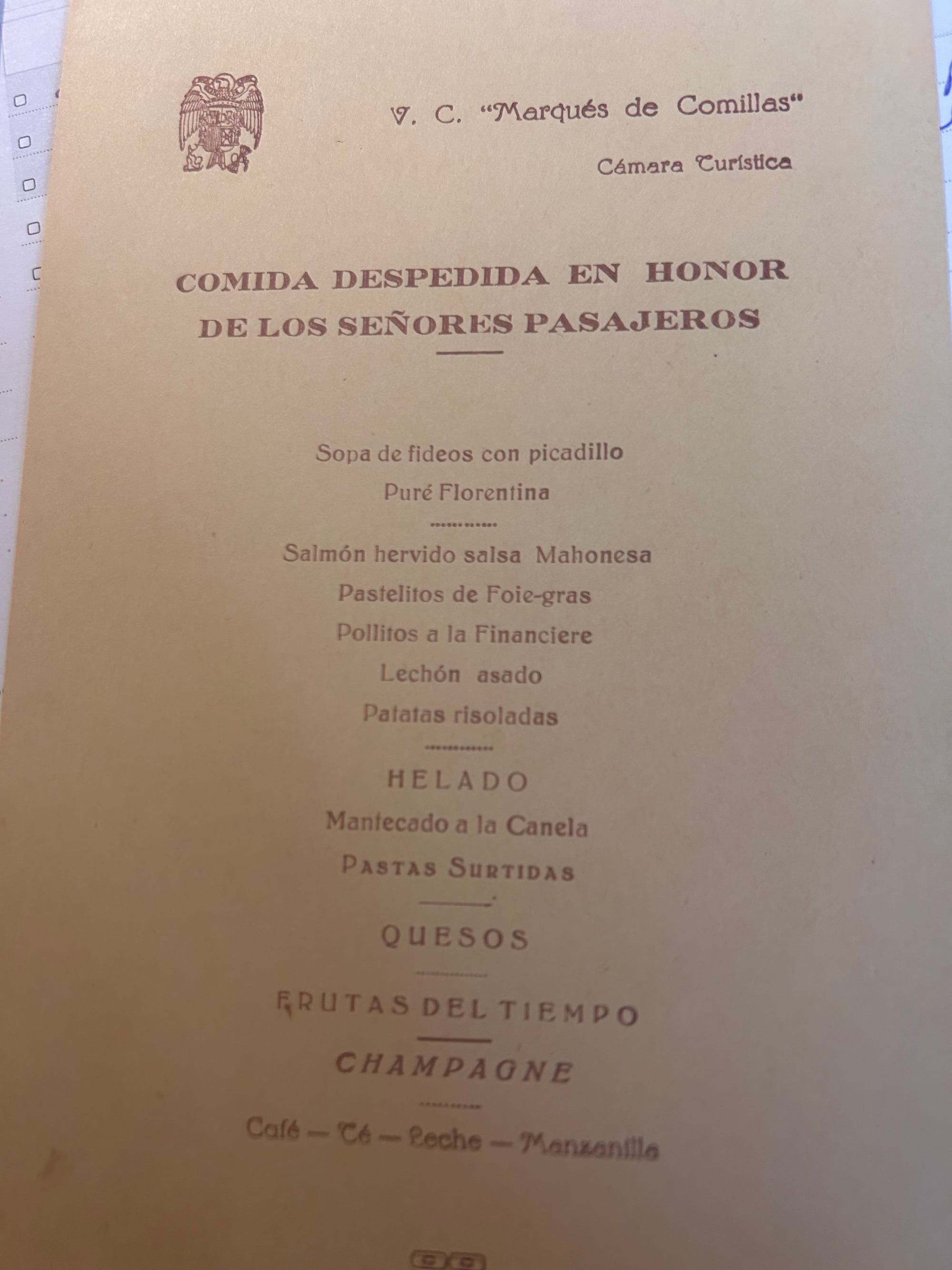

They traveled from Bilbao, in Portugal, to Havana (with a stop in Veracruz along the way) aboard the Marques de Comillas, a steamship operated by the Cuban Compania Transatlantica, which was operated by the state of Cuba.

My father wrote about Meillon being a place where people talked about food even if they couldn’t eat food; the ship’s menu may or may not have been followed to the letter, but I’m sure my father, Hilde and Walter were amazed and grateful for all of it, regardless, after what they had been through in wartime France (the kindness and generosity of the people of Meillon notwithstanding!)

My father’s wife Hilde sadly lost her life two years later, as I’ve discussed elsewhere. My father plugged along with his, notably for the sake of his son Walter. But however momentary the respite turned out to be, they were finally free of Europe and its wars and pogroms.