For the Poor and the Stranger

Paul Mirat didn't need Leviticus to tell him the right thing to do

We have a lot for which to be grateful; we’re alive.

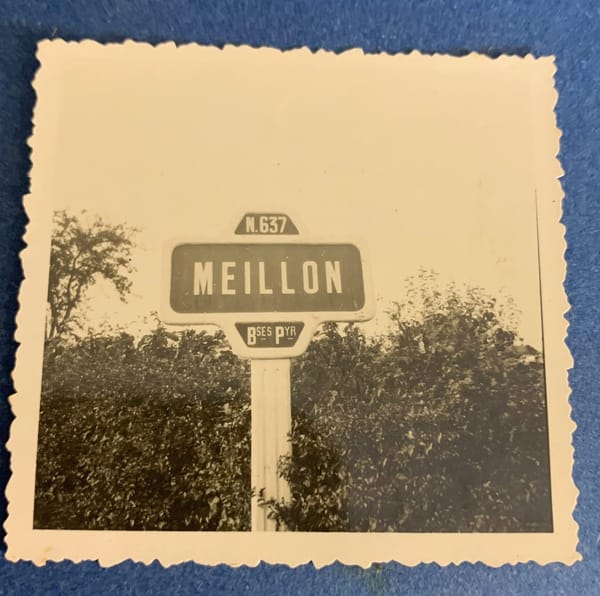

Me, above all, I’m grateful to Paul Mirat, who in 1940 was the mayor of a small French village called Meillon, and who helped save more than 2,000 refugees – including my father – by taking them out of the nearby Gurs internment camp and finding them homes among the 600 residents of his town.

Some of this is described in my memoir, The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family’s True Holocaust Story. (Please consider ordering it if you haven’t already (and if you have, thank you; if you liked it, please give it a rating on Amazon, and if you have, you have my most sincere thanks!))

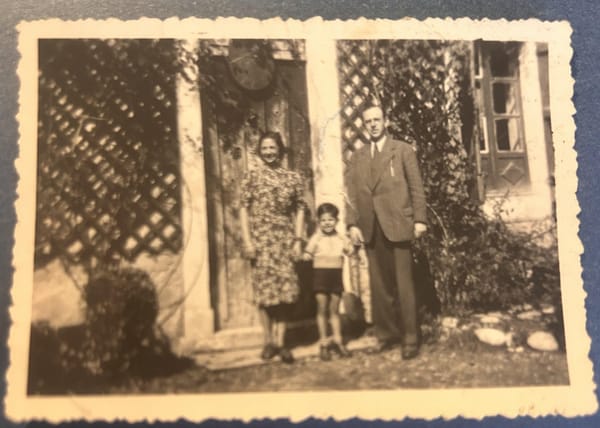

Mirat went so far as to rent an apartment for himself and his wife so that his home and stables could be used to house refugees (again, including my father).

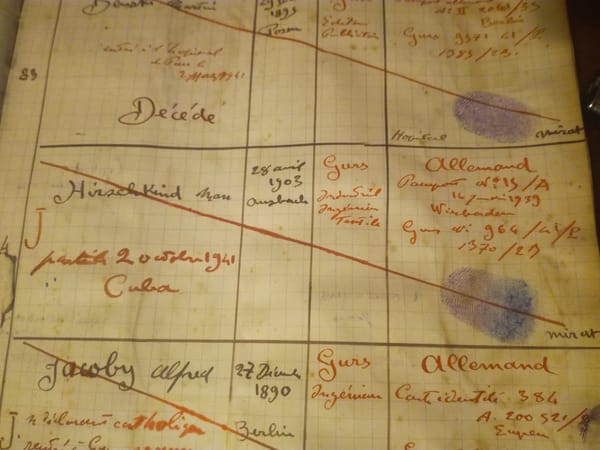

I know this thanks to Mirat’s grandson, also named Paul, who welcomed me a few years ago, and cooked me a delicious lunch, allowed me to visit the place where my father lived, introduced me to an elderly couple who had been alive at that time, and showed me the register his grandfather used to record the names and photos of the people who were thus saved.

Mirat couldn’t stand the idea of anybody having to live in an unsanitary internment camp, having seen firsthand what that looked like during the Spanish Civil War, when his area had been home to its first batch of modern-era refugees.

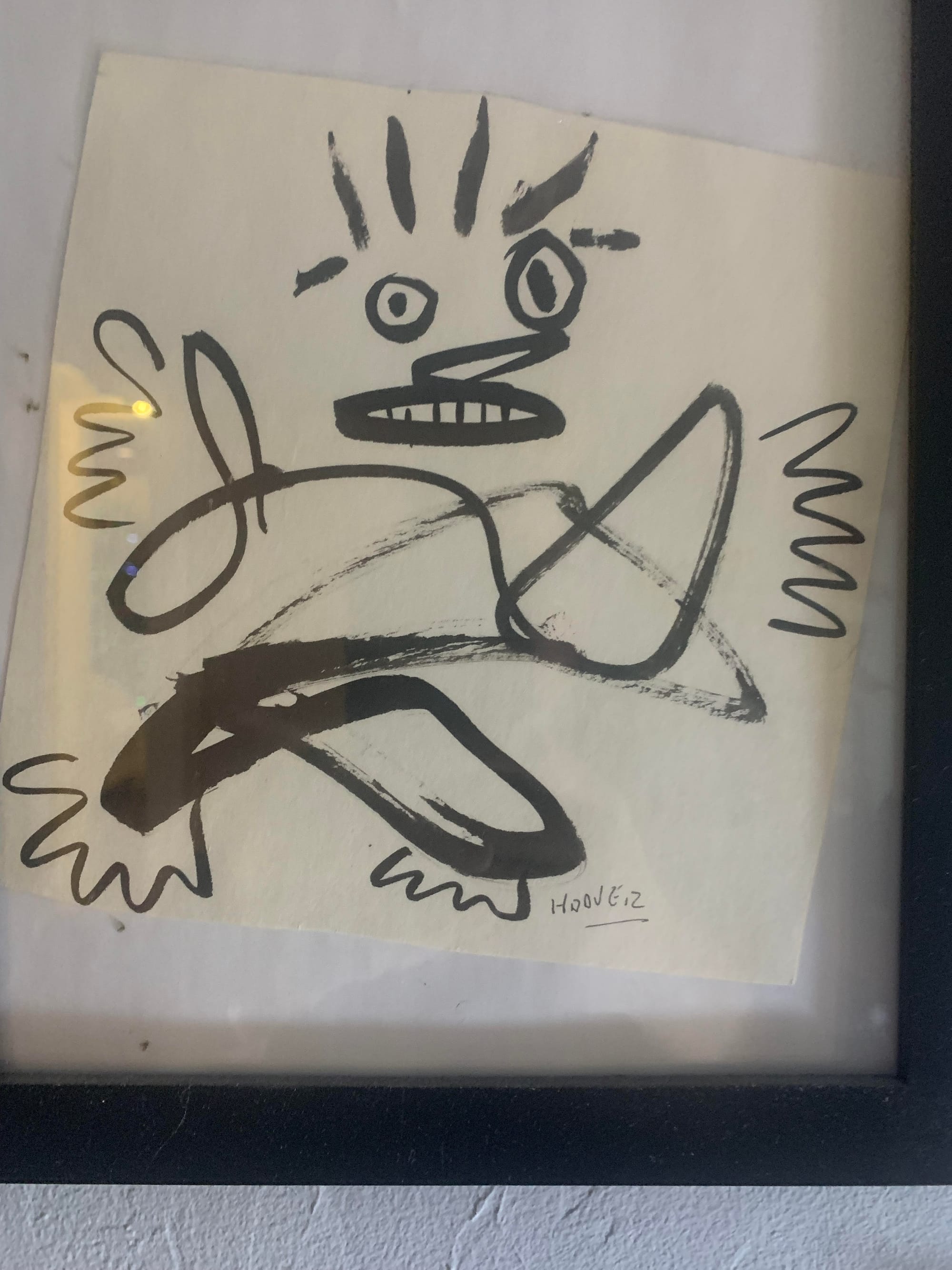

The photograph at the top of this newsletter was taken by my father, and is signed on the back “To Max Hirschkind, with friendship, Paul Mirat.”

The two men to either side of Paul Mirat are a local priest, Auguste Daguzan, and an officer in the Vichy cavalry named Bergès.

According to Dominique Piolet, Daguzan (1884-1956) was an ordained Catholic priest, a teacher and was notably responsible for the Jeunesses Chrétiennes – the Catholic Youth movement of the 1920s and 30s. In 1936, he was appointed vicaire général – vice-bishop – of the Basses-Pyrénées, a position that took on even more importance when war broke out in 1939 and the department was cut in two by the Demarcation Line in 1940.

Also according to Piolet, Dagusan “was a resistant – not in a military way, but by his attitude and his writing against the Nazis and the decisions of the Vichy regime, in particular concerning the Jews.”

One letter found in local government archives shows that Dagusan arranged for 53 Jews to live in Meillon (outside the Gurs internment camp).

He was arrested by the Gestapo and deported to the Nazi concentration camp of Dachau in June 1944, and was there until the liberation of the camp by American forces at the end of April 1945.”

Bergès, the military man, was an officer in the cavalry. Given the company he was keeping in this photo, he was unlikely to have been a staunch supporter of either Marechal Petain or his fascist prime minister, Pierre Laval. (It’s worth noting that after the war, Laval, who organized the most brutal and effective round-ups of Jews in France, was executed for his crimes, while Petain, the nominal head of state, had his death sentence commuted by de Gaulle.)

The three are standing in front of Paul Mirat’s house. The Mirats have been living there for eight hundred years. It is my fervent hope that they live there for at least another eight hundred.

The title of this newsletter is taken from the book of Leviticus, and urges us to care “for the poor and for the stranger.”

Paul Mirat didn’t need a Biblical injunction to do what came naturally. That generosity is in all of us, if we only allow ourselves to express it.