Gratitude for Tolerance

How a simple Basque beret stands in for a lifetime of thanks

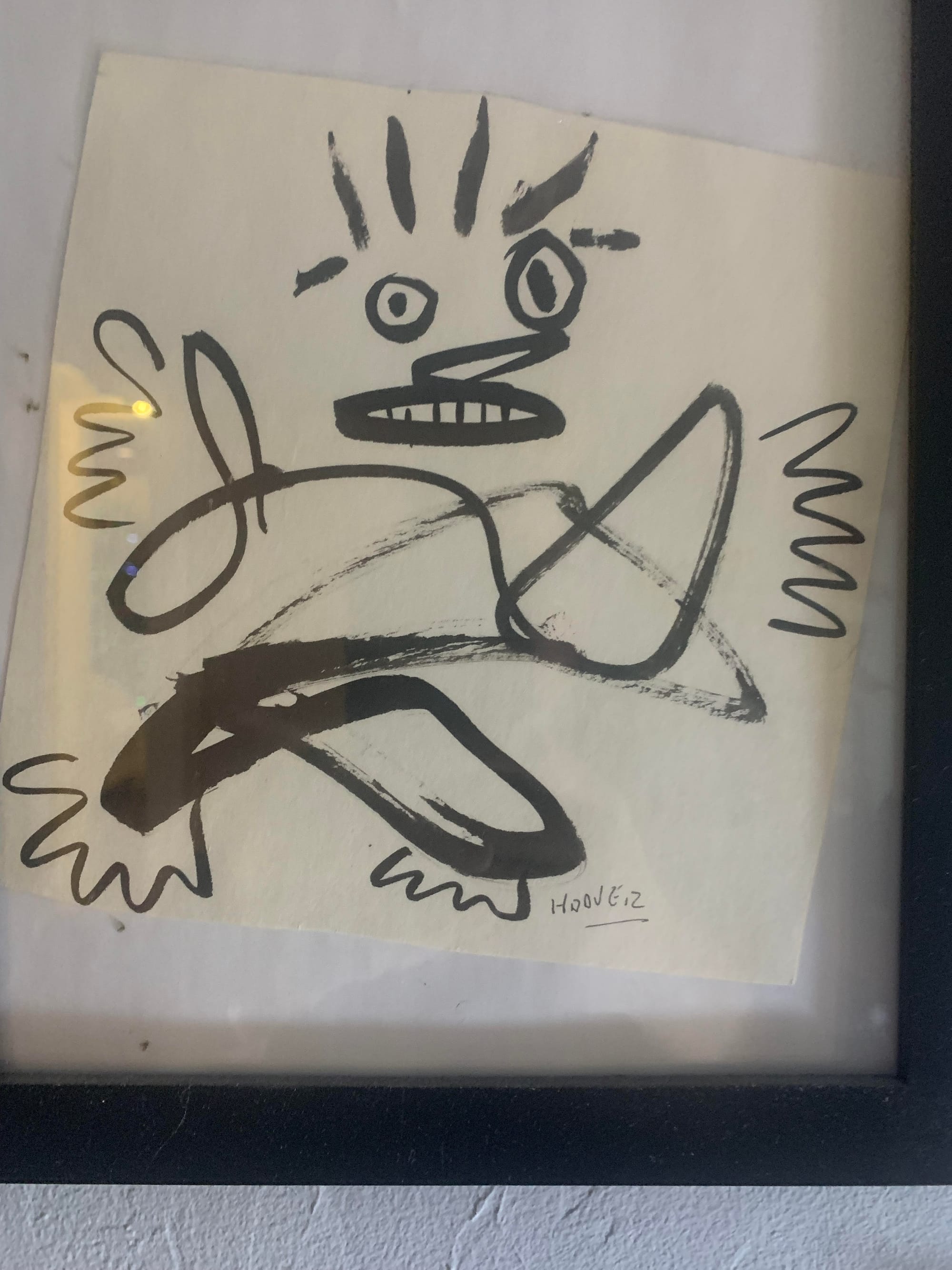

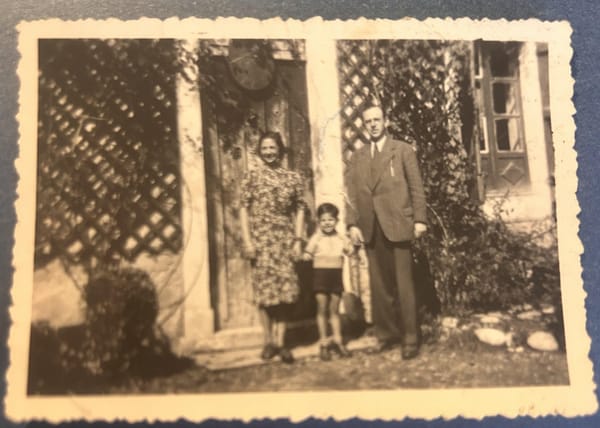

I’d seen my father wear a Basque beret from time to time over the years. The photo at the top of this post was taken in the mid-1960s, when I was under 10 and my father hadn’t yet been diagnosed with the bladder cancer that would kill him in 1976.

He wears the beret jauntily, but without irony or other apparent affect. It seems wholly natural, as if of course this German Jew from Bavaria would be wearing a Basque beret. (This was, after all, the same man who sent me to school in lederhosen, which in 1960s Queens meant making me a piñata, an object of forever ridicule for which my ears still burn with shame to this day!)

Or he could have been wearing one of those little alpine beanies like the one he was wearing in this other picture (alongside his older sister Beate, who looks like she’s staring into the abyss).

But it recently dawned on me that there was no earthly reason for my father to be wearing a beret. He wasn’t a beatnik, nor a fan of beat poetry. He didn’t play the guitar or listen to folk music. He wasn’t a raging francophile.

He was a man of another time – born in 1903, which is so long ago I like to joke that I was brought up by parents from the 19th century. “Civilized” people of his ilk didn’t cos play from other cultures.

So what was he doing wearing a Basque beret?

It was an expression of gratitude.

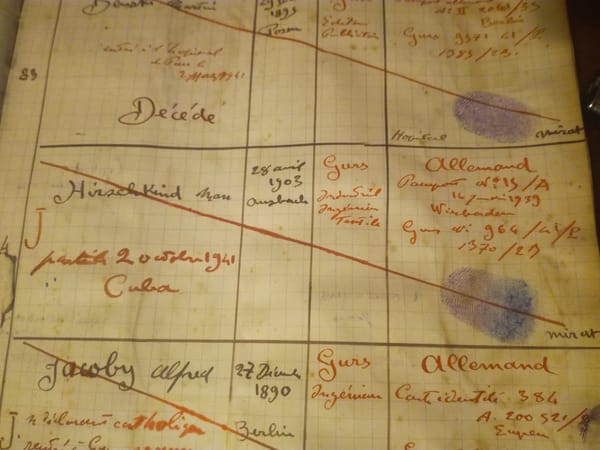

After Germany invaded neutral Belgium, my father was arrested in Brussels as an undesirable foreigner. He was sent to an internment camp for refugees in southwest France, close to the Spanish border.

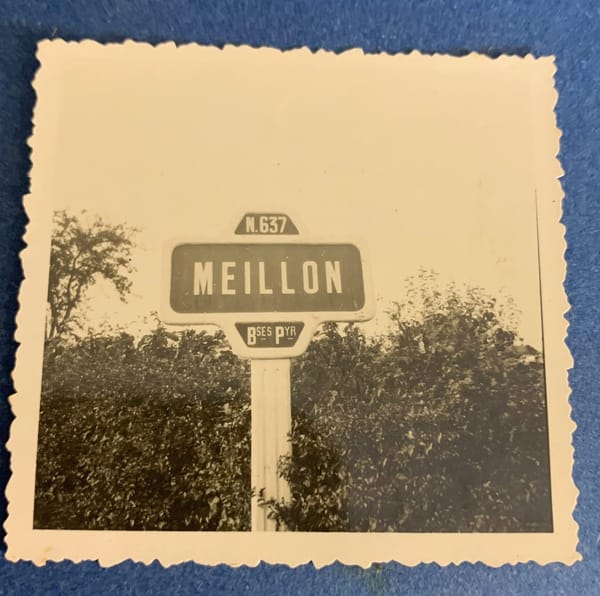

He didn’t have to stay in the camp for long, however, thanks to the intrepid and generous actions of Paul Mirat, the mayor of Meillon, a small town located close to the camp.

Meillon, as Paul Mirat’s grandson Paul would tell you, is in the heart of the Bearn region, also known as Basque country.

Paul tells me that his grandfather was greatly moved by the plight of Spanish refugees who came through the Basque region in 1936, scarcely four years before the Germans invaded Belgium, and were herded into these sordid camps.

Moved to action by the terrible conditions of the camps (where diphtheria, typhus and other illnesses raged), and by his empathy for the humanity of the refugees, Paul Mirat devised a system that allowed some 2,000 refugees (including my father) to live in a real home instead of the camp.

That act of humanity and generosity in turn provided those lucky refugees with a clean, well-lighted place, and resources (like paper and stamps) to write letters, fill out visa applications, and undertake other bureaucratic tasks that would have been nearly impossible from inside the confines of a refugee camp.

Paul Mirat wasn’t driven by a particular love for Belgians – or Jews, for that matter. However, he was a modernist, and in its most noble sense, modernism recognizes that everything is subjective, and that all perspectives are equally valid and must be tolerated.

Today, as society becomes increasingly hermetic and obliterates the lessons of modernism, it’s more incumbent upon us than ever to uphold the values of tolerance handed down by true heroes like Paul Mirat.

And we owe them our gratitude.

I’m convinced that wearing a Basque beret was my father’s way of paying tribute to a man and a people who did much to save his life. Of expressing his gratitude, however privately.

For Paul Mirat’s actions, and for those of his grandson, who upholds the memory of his grandfather and of the history of the Bearn/Basque region, I am truly grateful.