Safe Passage During Wartime

The examination of an oxymoron

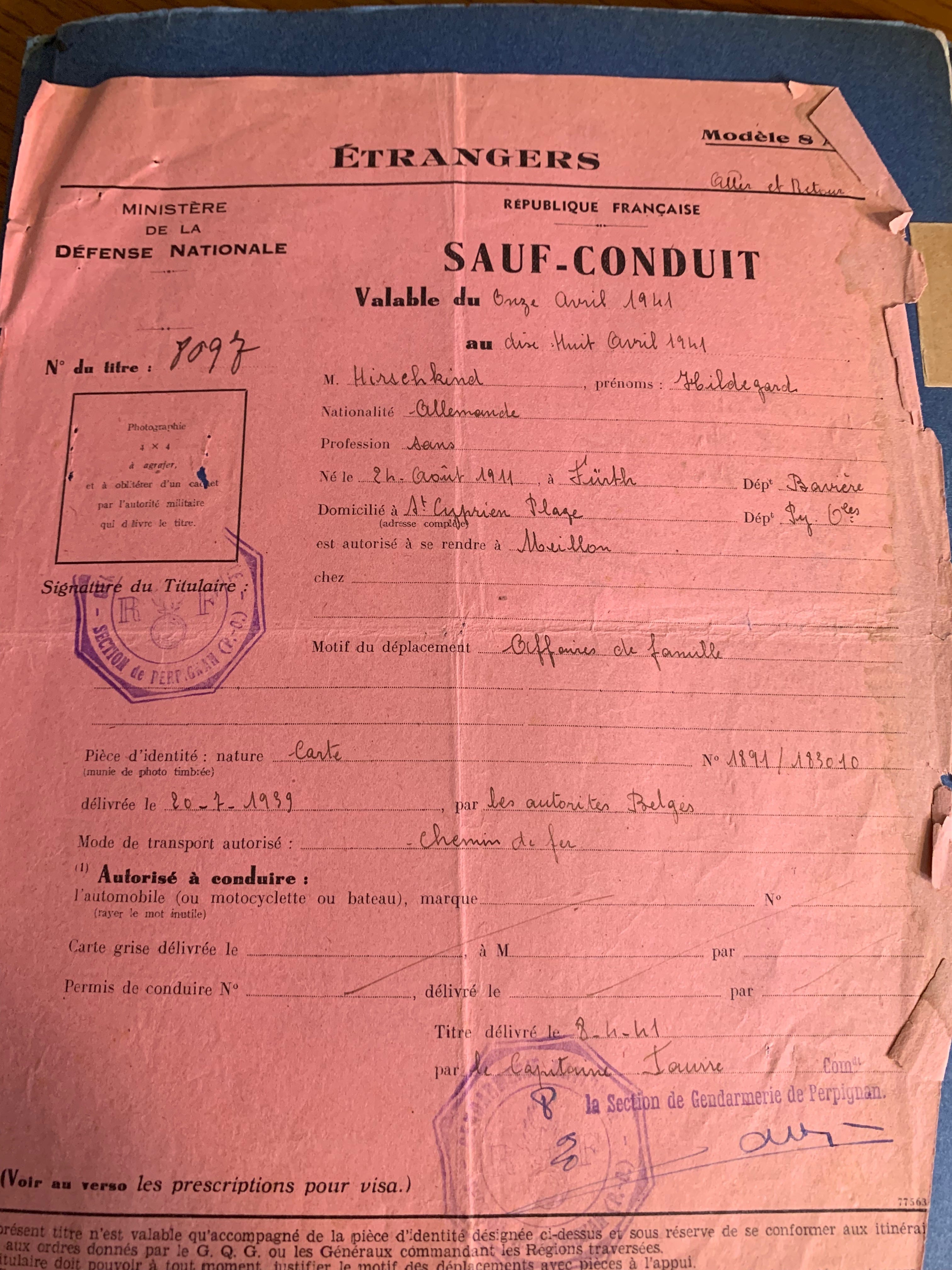

One of the documents that turned up during my research, and which inspired and became part of my memoir, The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family’s True Holocaust Story (Amsterdam Publishers, June 2023), is a safe-passage issued by the French authorities in Perpignan, a small town in southeast France, very close to the Spanish border (see my translation below).

I’m focusing today on this document because of how it relates to the horrifying events now unfolding in Israel.

The sad cycle of history

As the current conflict unfolds in all its horror, Egypt has discussed plans with the United States and others to provide humanitarian aid through its border with the Gaza Strip, but rejects any move to set up safe corridors for refugees fleeing the enclave, the Guardian reports.

Jewish or not, we should all feel the precarious nature of our existence. The ability of civilians to flee a conflict is a human right -- one we take for granted, but should not. As this document serves to illustrate, travel during wartime is difficult at best, and usually frightening and confounding. Issued to my father’s first wife, Hildegard Hirschkind (my father’s name before he changed it to Hickins), the safe passage is an artifact that reminds us of the precarity of what we consider our norms.

Why did Hildegard Hirschkind, a German Jew, need a safe passage in France? Here is a rough timeline of wartime events affecting my father, his wife and their infant son (aged 4):

- June 7, 1939, the Hirschkinds sought refuge from the Nazis by fleeing to Belgium;

- They lived in Brussels until May 10, 1940, when all foreign males over the age of 16 were arrested by Belgian authorities;

- Some 4,000 males, including my father, were sent to internment camps in France;

- My father was sent to the internment camp in Saint Cyprien, in the Languedoc/Roussillon region in southeast France, close to Perpignan and the Spanish border;

- Hilde, with Walter in tow, braved artillery fire and a variety of fraught border crossings (from Belgium to France and then from occupied France to so-called Free France—aka Vichy France) in order to join him;

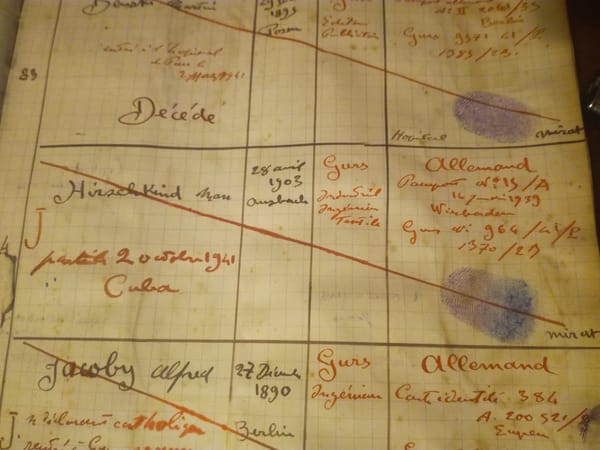

- Hilde was arrested along the way as an undesirable alien and sent to a different internment camp called Gurs, in southwestern France, also close to the Spanish border, but some 400 kilometers (~250 miles) to the west;

- Hilde was released on July 22, 1940, for medical reasons, and found a place to stay in Perpignan, at the home of a labor union member named Willy Bignals. She was thus able to “visit” with her husband Max — across a barbed wire fence;

- On October 19, 1940, the Saint Cyprien camp was flooded by unusually powerful storms devastating the Languedoc and Roussillon regions, forcing authorities to evacuate refugees to Gurs;

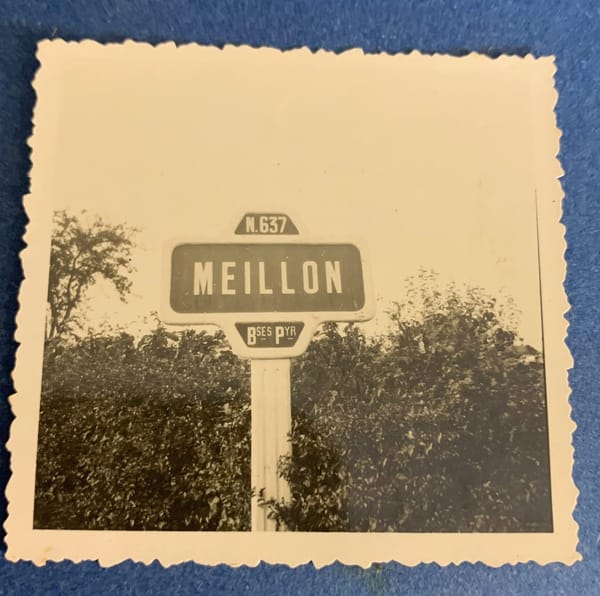

- In February 1941, Max obtained permission to live in Meillon, a town close to the Gurs camp, and stayed at the home of Meillon’s heroic mayor, Paul Mirat;

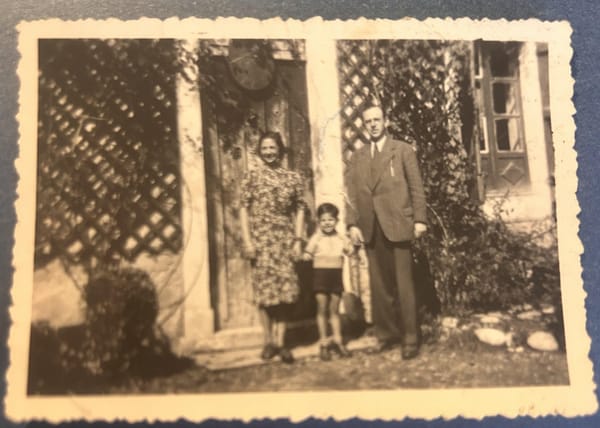

- Hilde, meanwhile, was forced to remain in Perpignan with Walter until receiving this safe passage in April 1941, which enabled her to finally reunite their family after six months of constant effort.

One can only imagine the fear and the challenge of trying to find information about a loved one, trying to speak with officials besieged by similar requests from wives and children of hundreds or thousands of other families, many of whom didn’t speak a word of French; of trying to travel without proper documentation; of living in fear of losing one’s child; of this child suffering from respiratory illness; of shuttling him from one cold, winter wind-swept refuge to another, all while trying to keep open channels of communication and information; of trying to send and receive letters at uncertain addresses; of putting one’s lives in the hands of postal workers and other civil servants who may or may not have had sympathies for Jews, or for nationals of a country that was invading theirs; of begging food from people who were themselves deprived.

A rough translation

The safe passage was issued to Hildegard Hirschkind by the French Ministry of National Defense on April 8, 1941, and was valid from April 11 through April 18 of that year. It lists her nationality as German, and states that she was born in the Bavarian (Germany) town of Furth.

It further states that she was domiciled at St. Cyprien Plage, an internment camp in the Pyrenees Orientales department.

It states “family business” as the reason for her travels, and that her proof of identity is an ID card issued by the Belgian government on July 20, 1939. It says that she is only authorized to travel by train, and she is specifically barred from driving a car or motorcycle.

The safe passage was signed by the captain of the gendarmes [police] of the Perpignan region.

The document lists her nationality as German, although the Nuremburg Laws of 1936 stripped her (and other Jews) of their German nationality. But French authorities relied on the Belgian ID card to establish her identity, and as far as the Belgians were concerned, she was German.

History is personal

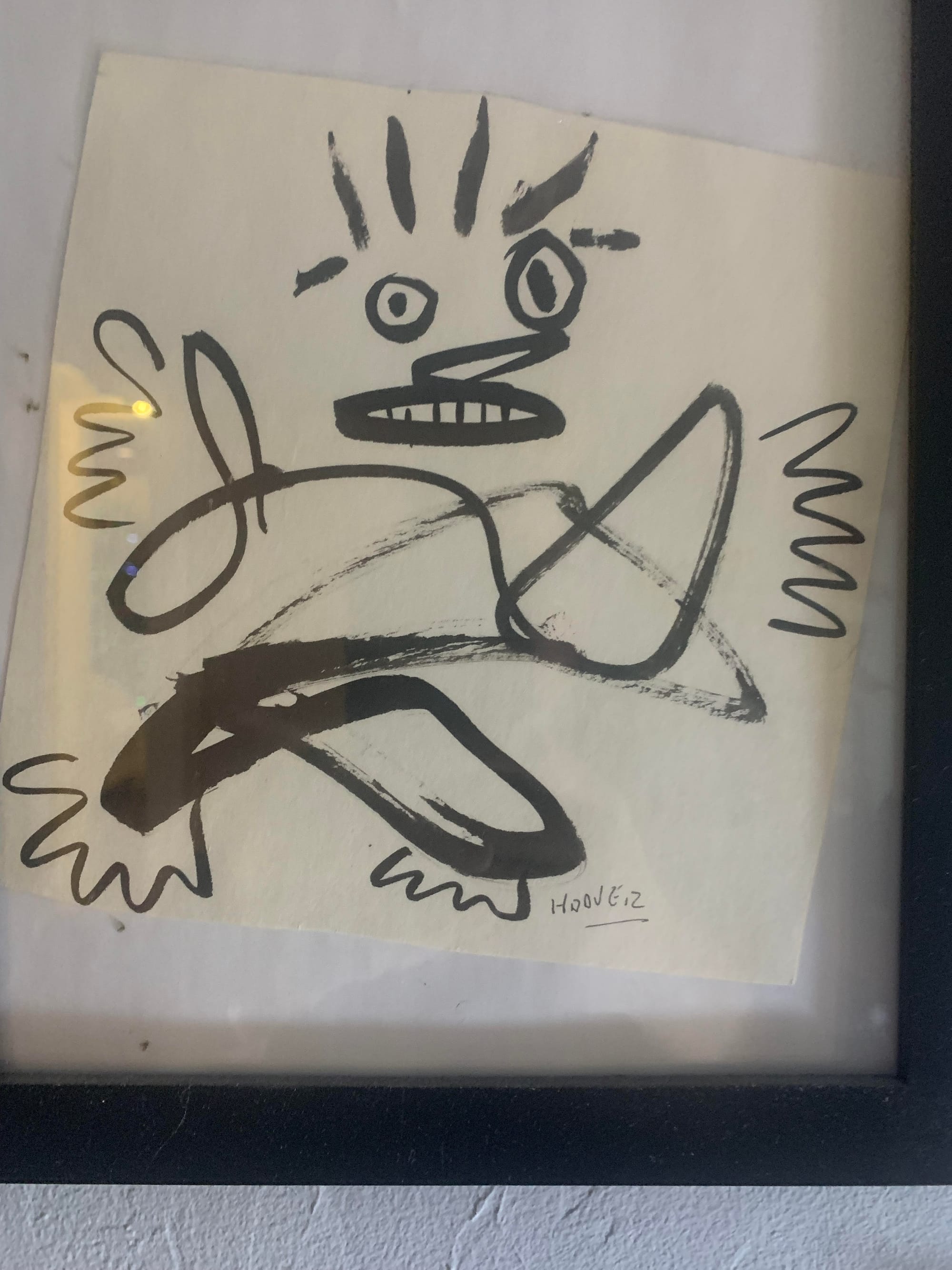

There is also a blank square where a photo of her face was once stapled. I believe it was my father who removed it, for he never forgave his wife for later betraying him with a former lover, and in fact suspected that their son might not really have been his. I had never seen a single photograph of her until my 2019 trip to Meillon.

While he kept this safe conduct, he could not abide to see her face.

The personal always supersedes the political.

I can only speak for myself: the very fact of my existence is itself a statistical anomaly; and all around me I see people willfully dismantling the structures enabling peaceful change, civility, and the rule of law, and I see our continued existence as a species under growing threat from climate change, isolationism, and jingoism.

For as long as I can remember, threats to the common – global -- good seemed to be anomalies that could be and were usually addressed through a post-war consensus among the global powers. Now, consensus is lacking, moral authority is waning, globalism is a dirty word, and the forces of chaos are gaining the upper hand. Peacemakers such as Sadat and Rabin are routinely assassinated, and just as routinely, their followers turn for leadership to warmongers.

And as a Jew, I see the burgeoning threat that my father always feared would come to these shores too: authoritarianism and its ever-present concubine – antisemitism.

And no one should be surprised when erstwhile Israel hawks begin attacking Israel for having provoked this attack, and accusing American Jews of having divided loyalties or of dragging “real” Americans into foreign wars; Jews will always be scapegoats for those who would divide their country.

For people trapped between warring parties, there is no safe passage. In fact, there is no safe passage for anyone, and there is no asylum, and there is no neutrality. For anyone who thinks and feels like a human being, there is only the oxymoronic hope that things will revert to an imagined more perfect state, that things will get better because they always do, that because we are alive we were meant to be, and that there is therefore a purpose to our existence that will be revealed to us in due time.