The Holiday of War

Hanukah celebrates an act of war and a fight for high office. Light a candle in memory.

Hanukah is always celebrated in the US during a time of Christmas spirit and holiday cheer, but it is truly a holiday that commemorates a clash of civilizations. Sadly, no one truly wins such a clash, but we still light the candles.

As explained more fully by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, Hanukah celebrates the victory of the Maccabi-led Judeans against the Seleucid (aka Syrian-Greek) empire in around 167 BCE. As most people know, Hanukah celebrates the miracle of sanctified oil that burned for eight days longer than expected – hence the moniker “festival of lights.”

The Maccabi were fighting for more than just the right to re-establish the Temple; they were fighting for the right to be Jewish, to observe the Sabbath, to eat kosher, and even to circumcise one’s children. For all intents and purposes, it was a fight to preserve the very essence of Judaism (and, it must be said, to protect Jonathan Maccabi’s claims on the high priesthood).

This year, the celebration of Hanukah occurs as Israel continues this existential fight. But we don’t light the candles to celebrate war — we light them for a different reason: the holiday is about the generation of children of the diaspora who can hope for better times. The traditional Hanukah song Mo-oz Tsur (Rock of Ages) closes with the lines, “children, whether free or fettered… the time is nearing which will see all people free, and tyrants disappearing.”

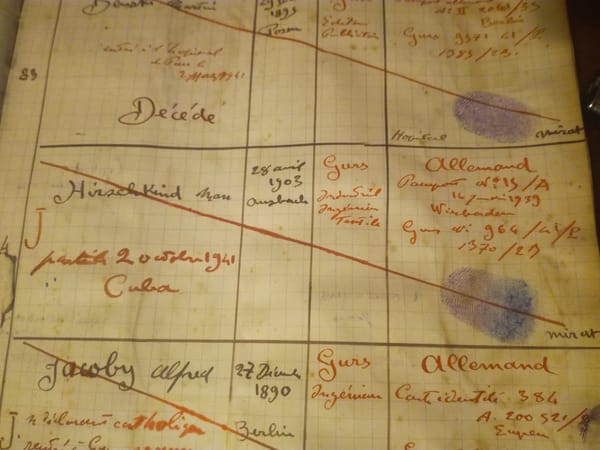

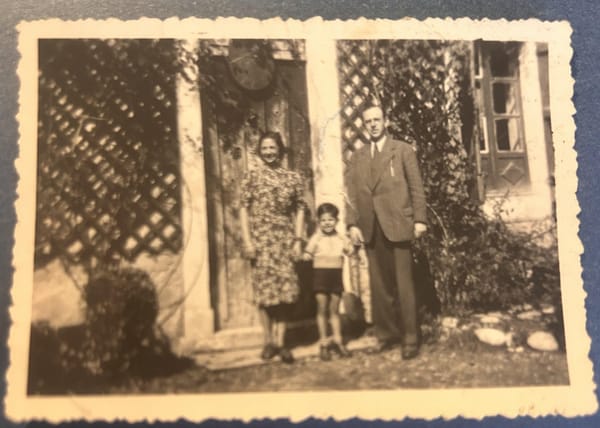

The photograph at the top of this post is of my father’s first wife, Hilde Hirschkind, and as far as I know, it’s the only remaining picture of her. It was used to identify her while she was imprisoned at the Gurs internment camp in southwest France.

Hilde Hirschkind nee Bomeisl was born in Furth, Germany, on August 24, 1911, and died May 14, 1944, in Havana, Cuba. Her father, Leopold Bomeisl, owner of a toy factory in Nuremberg, Germany, was murdered on May 21, 1943, at Sobibor, the same death camp where my father’s mother Dora perished.

The streak of red dots discoloring the right side of the photograph are like the splatter that bloodies survivors for generations. Not just survivors of internment camps, or of genocide, but survivors of all wars. War doesn’t just change people – brutalizes them.

Hilde survived the war, at least long enough to emigrate to Cuba. (Cuba rather than the United States because their four-year-old son Walter suffered tuberculosis, so the US wouldn’t admit him.)

She drowned in the sea. My mother told me that while the death was officially ruled an accident, the truth was she had killed herself. Why? Because, again according to my mother, she had been caught by my father in the arms of her former lover – someone she had dated in Germany before meeting my father, and who was a fellow member of the “international community” in Havana.

She had been caught in that man’s arms, and my father (supposedly) said he wouldn’t give her a divorce for the sake of their son – but that they would no longer have sexual relations. The discovery of their liaison also caused him to wonder if Walter were actually his biological son.

So did she kill herself? Because of an infidelity? Because my father wouldn’t have sex with her? Because she couldn’t be with the man she truly loved? Or because her father was killed in the extermination camps the year before?

Did she even really kill herself? Apparently, she was not a swimmer and afraid of the water, so an accidental death while going for a dip seems out of the question. The death was ruled an accident – apparently my father prevailed upon the coroner to issue that finding – again, for the sake of the child.

Then, my father moved Walter (my half-brother, in case that isn’t clear) to the US, where they shared an apartment for a time with a wealthy friend, Henry Wolfe, along with Wolfe’s wife Marianne, and their son. But Walter couldn’t abide the situation – he fought with his pseudo-sibling and claimed Marianne always took the other boy’s side.

Unsaid and unknowable: did my father’s suspicions about Walter’s true parentage exacerbate a rift between them that became more pronounced once my brother’s sexual orientation became clear?

Later, as a young teen, Walter was entrapped by a NYC vice squad cop who coerced him into undoing his pants at a hotel near Union Square. As punishment for being gay, Walter was sentenced to attend a Quaker high school in Pennsylvania.

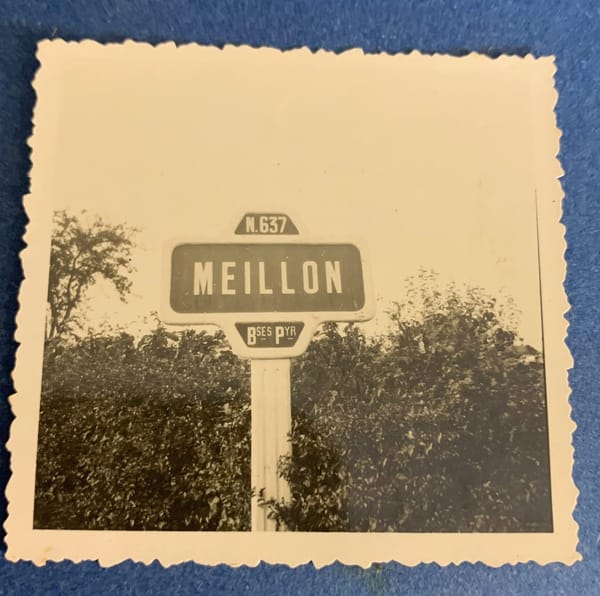

So Walter went from a life of relative ease in Germany to one of precarious flight across Belgium, through the battlefields of northern France, through an internment camp in southwest France, to Havana, followed by the death of his mother, enforced cohabitation with a rival, the humiliation of a public trial (at the age of 14), and then exile to a different state from where his father lived.

Where were the grownups in all of this? Where was the solace? The empathy?

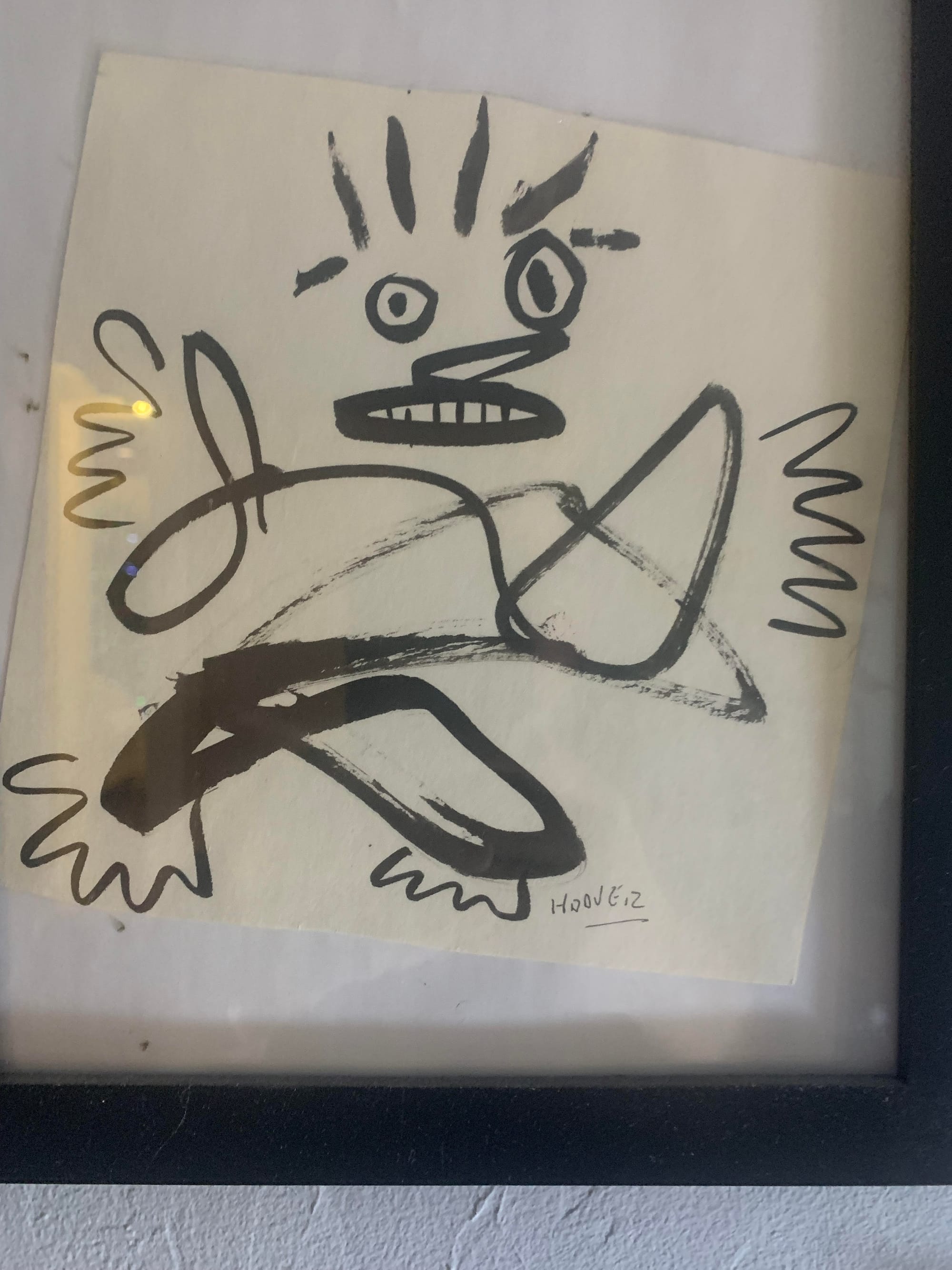

Walter grew into a terrific artist and artisan, before dying of AIDS in 1985.

He didn’t have a happy life, although I think he did have some moments of joy. I think he loved his longtime companion, a man named Tom.

But I suspect he never ventured far from the splatter of blood that flecked his mother’s cheek on this photograph taken at an internment camp in France.

This year, I will be celebrating Hanukah with my seven-year-old, but I know that the children of Israel and Palestine are suffering, and will continue suffering long after this war is over. In many ways, this Hanukah marks the first year of how their lives changed forever.