The Interpreter of Internment Camps

An examination of a certificate attesting to my father's service in a French internment camp.

My father, while imprisoned at an internment camp in France, got a job as an interpreter, facilitating conversations between the French guards and the German- and Flemish-speaking prisoners whose fates hung in the balance.

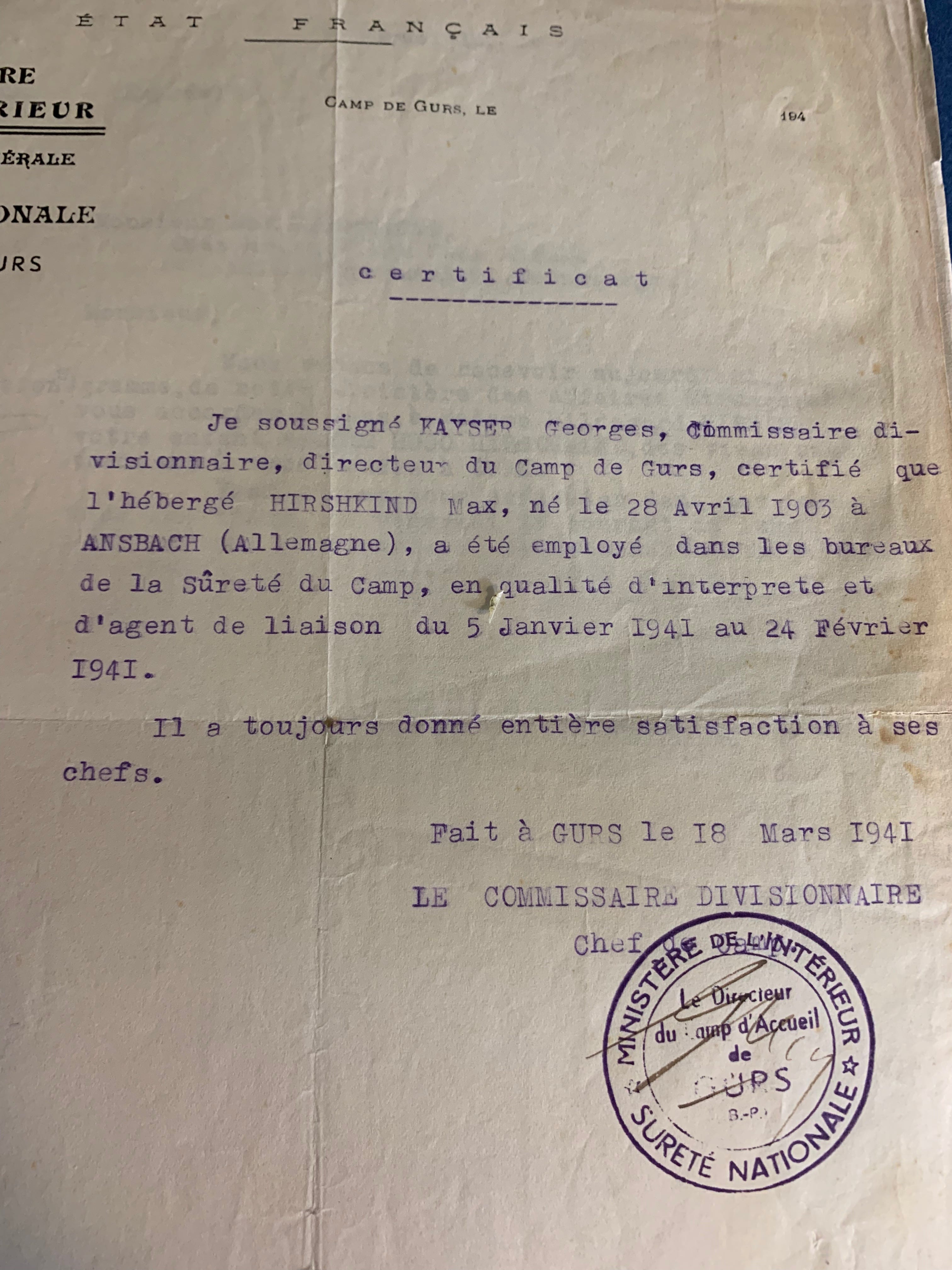

Here’s the document [translation below] issued to certify his service as an interpreter:

Here’s the English translation:

French State – Gurs internment camp, dated [blank]

Affidavit

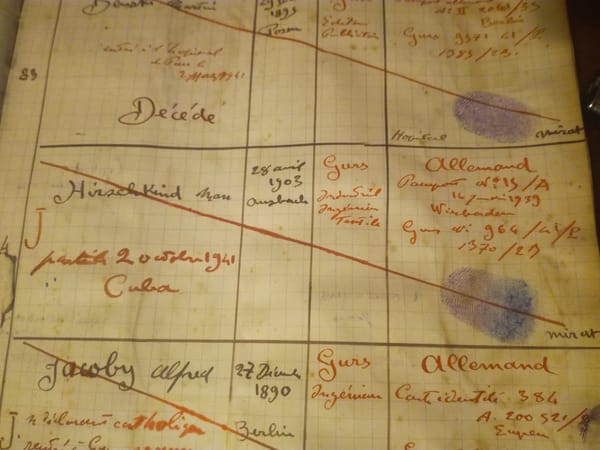

I, the undersigned George Kayser, divisional commissioner and director of the camp at Gurs, hereby certify that internee Max Hirshkind [sic], born April 28, 1903 in Ansbach, Germany, was employed by the camp’s security office as an interpreter and liaison officer from January 5, 1941 to February 24, 1941.

He always performed his duties to the utmost satisfaction of his superior officers.

Document executed at Gurs on March 18, 1941

Signed – the divisional commissioner and director of the Gurs internment camp.

Stamped – Ministry of the Interior – National Security – Director of the Gurs internment Camp

(I write about finding this and other documents, and the events that followed, in my memoir The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family’s True Holocaust Story).

The document is printed on government-issue letterhead, with an official seal, but the paper is tissue-thin; it has also been cut out from a larger page that had been used before for another purpose. Wartime privation was no joke, even for the government.

I was struck by a number of other details, aside from the misspelling of his last name (which was Hirschkind, not Hirshkind).

- Notably, the officers are “his superior officers,” making him in some way part of their company. In this capacity, he wasn’t an illegal alien, or a detainee, or even a refugee – he was an active member of the security office. And it speaks to the ambivalence of the French state at the time – Nazified, but not fully Nazi.

- Also, he wasn’t merely an interpreter – he was more like a go-between or fixer. He was German and Jewish, but also someone who had lived in Holland and Belgium, spoke fluent French, and had traveled enough to understand the myriad complexities of living in a new place. It’s likely that he saved at least one person from dying because they misunderstood an order or an instruction.

- Finally, the term used by the French to describe the camp was “camp d’accueil,” which is literally “welcome camp.” I refuse to accept that euphemism in my translation; these weren’t concentration camps in the sense we give to the camps located in Germany and Poland, but they’re also not exactly refugee camps in the sense we give temporary shelters we build to help victims of natural or human-made disasters. Internees here had no more freedom of movement than prisoners in a penal colony.

The road to Auschwitz went through… southern France?

Like thousands of German Jews, my father had thought neutral Belgium would be a good place to go in 1940 when he fled Nazi Germany with his wife and four-year-old son.

On the very day Germany invaded Belgium in May 1940, the Belgian police arrested every foreign male over 16 years old and deported them to internment camps in Nazi-occupied France, from whence they would eventually be sent to Auschwitz or other death camps.

Many wives and children chased after their handcuffed husbands, on their own hook, through cannon and corpse riddled fields, following rumor and fortune, hoping to find word to or get word from or about their loved ones.

My father’s first wife, Hildegard, and their infant son Walter, my half-brother, were among them.

As my father wrote in a letter* in late 1941, “Through artillery fire they made their way to find husband and father.

“In June/July 1940, they themselves were interned at Gurs for seven weeks. Then they came to St. Cyprien-Plage, and until the end of October 1940 we saw each other nearly every day for a few hours, albeit under punishing conditions.”

The camp at Gurs was built out of wood, hastily and poorly, because another camp built on the beach at nearby St. Cyprien was even more unsanitary, even by wartime standards, as it flooded regularly from frequent winter storms.

Men and women, the elderly, and the young, German- and French-speaking, were thrown together in shanties organized in grids. Food had to be distributed and health care made available when possible. Few of these people spoke French, and fewer still spoke it well enough to make themselves understood. Sit there. Don’t go there! Instructions from camp security officers could be a matter of life and death.

In the same letter, my father wrote about an elderly family acquaintance named Dora Hecht (the letter, sent from a transatlantic liner taking him and his family to Cuba, informed Mrs. Hecht’s family of their Aunt Dora’s death); Mrs. Hecht was housed in the Women’s Barracks #9 of Women’s Lot K at Gurs), and my father notes that he visited her every fourteen days, except when he had to “give up the very scarce exit passes to fellow internees who needed to visit their wives and mothers.”

He says that after she died, her blouses “were bequeathed to occupants of the barracks who had been helpful and supportive to her.

“Woe is me when I think of the separation and the sorrow, the misery and the hardships of these dear ones – but may we persevere!”

* The letter was published in Exit Berlin, a history of one young woman’s fight to save members of her family stuck in Germany, written by American Jewish Committee archivist Charlotte Bonelli.

My half-brother Walter had tuberculosis. Hildegard was frail and sickly. Being in that camp was a mortal danger for them. Almost a thousand internees died of typhoid fever or dysentery.

Interpreting dire circumstances

In Germany and Poland, the Nazis thought it good fun to prop up select Jews as leaders or go-betweens for the prison camp guards. Dubbed “kapos,” these Jews prolonged their lives by making the lives of their fellow-Jews more miserable. (I recommend a brilliant and disturbing novel by Aleksandar Tisma, called Kapo.)

This wasn’t that. This was France. While the new French government, set up in the city of Vichy (a latter-day Avignon for displaced autocrats), marched in lockstep to Berlin’s drumbeat, the French were not in the business of killing Jews. Arrange transportation for them to go to their deaths – sure. But they had no stomach for killing them. Yet everyone was aware of what came next.

For the refugees, the challenge was clear: Either you found yourself an exit visa, or you found yourself on a train to Auschwitz.

And even if the life of a camp internee in France was quite different from one in Germany or Poland -- French refugee camps were not death camps -- the horrible sanitary conditions killed hundreds of people, mostly elderly, and some even died from suffocation when they slipped on the way to the outhouse at night and fell face-first into the muck.

Even without the looming threat of gas chambers next door, the terrified refugees were faced with having to navigate life in a hostile foreign country in a language they didn’t speak or read, needing to understand how to get food and water, where to clean themselves, when they were allowed to go to the latrines, and when and under what conditions they were allowed to have visitors, receive mail, or even leave the camp.

What an amazing stroke of luck to have found there someone who could help them overcome the language and cultural barriers to not only survival, but potentially a next step.

He performed his duties “to the utmost satisfaction of his superior officers.” No kidding – it was a matter of life and death for himself, his family, and for many of his fellow refugees.

My father had the good fortune of being a polyglot – he learned languages easily, and spoke 8 of them fluently. He was also – and probably not coincidentally – a very sociable and engaging man, and people tended to trust him. When he shook your hand, you felt this was a person whose word was good.

So what did this get him exactly?

Was it thanks to this facility – of performing a useful duty, doing it pleasantly and well, and ingratiating himself with others regardless of their station in life – that he was able to get his wife and child out of Gurs?

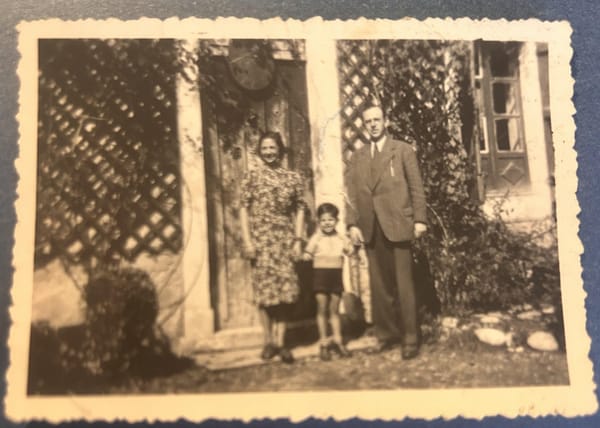

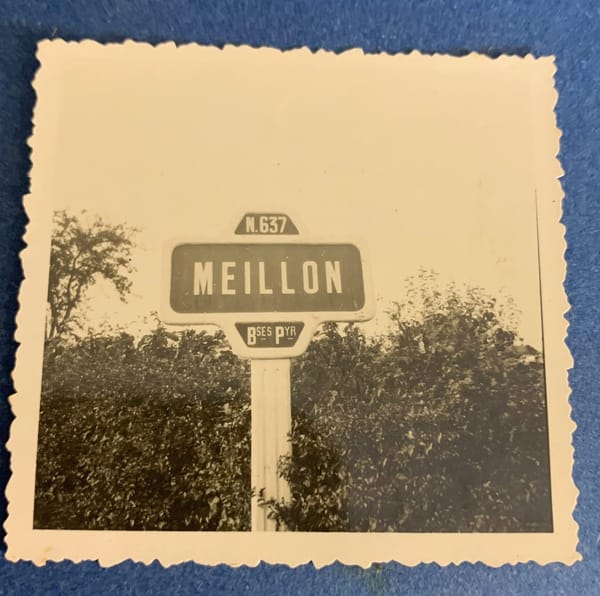

He, Hilde and Walter were allowed to live at the home of Paul Mirat, the mayor of Meillon, the town closest to Gurs; indeed, Mirat convinced the 600-or-so townspeople of Meillon to provide asylum for several THOUSAND refugees.

The US today places concertina wire and floating death traps in the Rio Grande river as “deterrents” to people seeking asylum on our shores. Yet our consciences are shocked by the cold-hearted rejection of ships full of Jews turned away at US harbors during WWII.

But let me return to Mayor Mirat and the citizens of Meillon. A village of 600 people gave asylum to thousands of refugees, most of them Jews, and with that asylum, a chance to catch their breath and apply for exit visas to the US, Cuba, or anywhere that would have them.

This was some of the work my father did at the camp, and for which he gave “utmost satisfaction” – not only to the French officers running the camp, but to his fellow refugees.

I know of at least one person for whom he helped arrange paperwork – and I know of it only thanks to an episode I recount in my memoir, The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family’s True Holocaust Story. My father never spoke about this – or about anything that happened in Meillon.

The reason for the existence of this document is something of a mystery. Who needed to see proof of my father’s work, much less that he gave “the utmost satisfaction” to his superior officers? Was it in order to prove to potential host country governments that he wasn’t indigent? Or an undesirable? Did he request it, or was it issued as a matter of course?

I’ll probably never know the answer, but it’s worth noting our instinct to record our actions, which dates back to while we were still living in caves.