The Ongoing Relevance of the Holocaust

Why I wrote a memoir and why I'm still writing it as we speak

One of the first things I tell audiences when I talk about my book, The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family’s Holocaust Story, is that I’m very aware of the incongruity of someone born in 1961 writing a Holocaust memoir.

The thing is, it isn’t exactly a Holocaust memoir. It’s a memoir about a particular journey across a series of geographies, psychologies, and generations. And as particular as it may be, I have also found it to apply generally to many people, in many countries, of many generations.

One reader, a survivor herself – she was a so-called hidden child in France – confessed that my memoir made her reconsider her anger towards her father, also a survivor, whose continued faith in God she couldn’t reconcile with the human tragedy they witnessed first-hand.

Another reader, like myself a generation removed from the Shoah, shared his frustration with the yawning gap between what really happened and what we were told. How, well into adulthood, we’ve continued believing many of the things we were told as children – things that were said to protect us from grim realities, or (more maddeningly), to protect the tellers from reliving their trauma.

As a former journalist -- and to this day a writer of short fiction and novels -- writing about the Holocaust was not something I had planned on doing.

Like for many of my contemporaries, I suppose, the Holocaust was a thing that happened a long time ago, to other people, some of whom might have been members of my family. It’s not that I minimized what it was, or the importance it played in the history of the Jews, in European history, American history, and the history of Israel – but it was history.

It didn’t seem especially relevant to me, to now.

Then, about four years ago, I received an email from someone I didn’t know – a nephew named Luis, as it turns out. I didn’t know he existed, and vice versa. Not only that, he had never met his father (a half-brother I never met either) and had never so much as seen a photo of this man. He only wanted one thing from me and that was a photo of his dad.

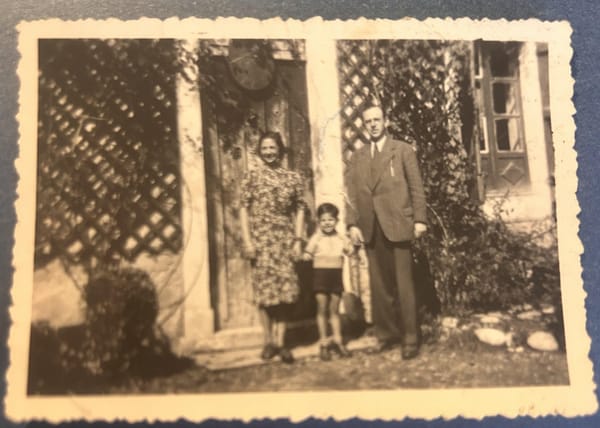

I had in my possession a metal box my mother had instructed me to look at after she passed away, and which turned out to contain a bunch of old photos, folded cardboard report cards, divorce decrees from long-ago husbands — you know, dusty stuff no one cares about. Dutifully after she died, I looked through the box and then stuck it in my basement.

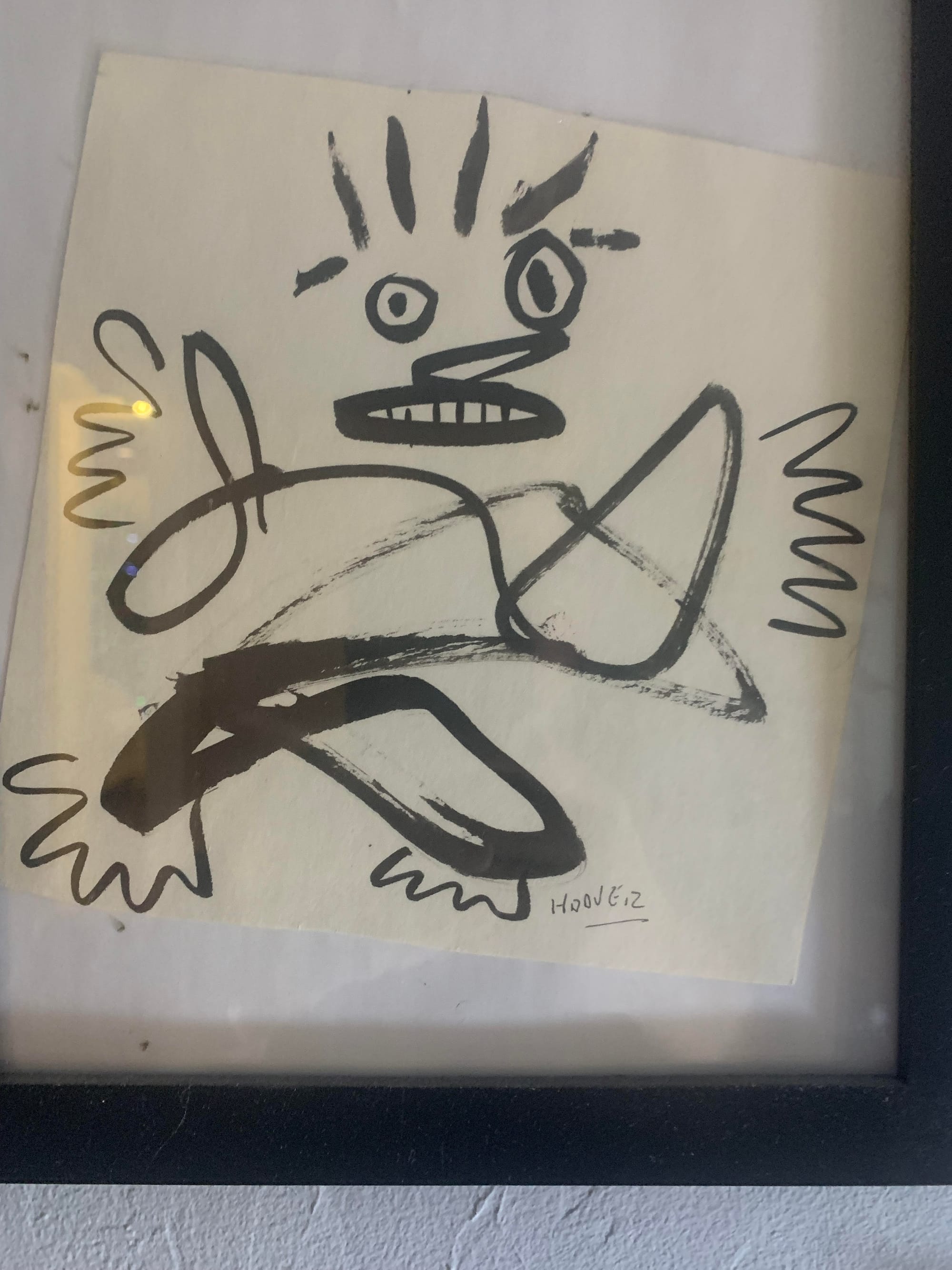

So after reading Luis’ email and calling him and expressing my joy and amazement, I went down to the basement to find a picture of his father, my supposedly crazy half-brother Johnnie. (I say supposedly because I don’t have first-person proof of his craziness, not because there isn’t ample evidence to support that claim. I’m just trying to be precise with my language because he’s dead and no longer able to defend himself, and also because his ghost might be a craaazzzzy ass vengeful goblin, you just never know.)

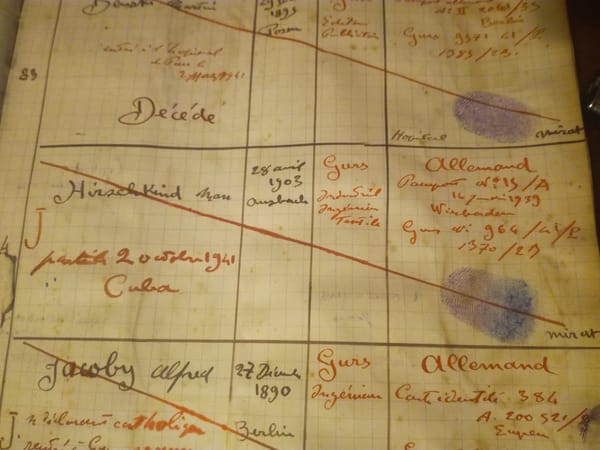

I did find several photos of Johnnie, which I sent along to Luis. But I also found other papers and documents that struck me as odd or surprising, especially as they seemed to have been kept carefully and selectively for many decades, but with no word of explanation to me as to their meaning or import.

That led me back upstairs to my computer, to Mr. Google, where I started searching for names and places cited on some of the documents I was finding.

And lo and behold, I stumbled upon the website for the Kupfer silk factory in Ansbach, the tiny German hamlet where my father grew up. Kupfer was my maternal grandmother’s name, and her father was the founder of this silk factory. And imagine my surprise to see that on their website, they claimed to be family-run for more than 135 years.

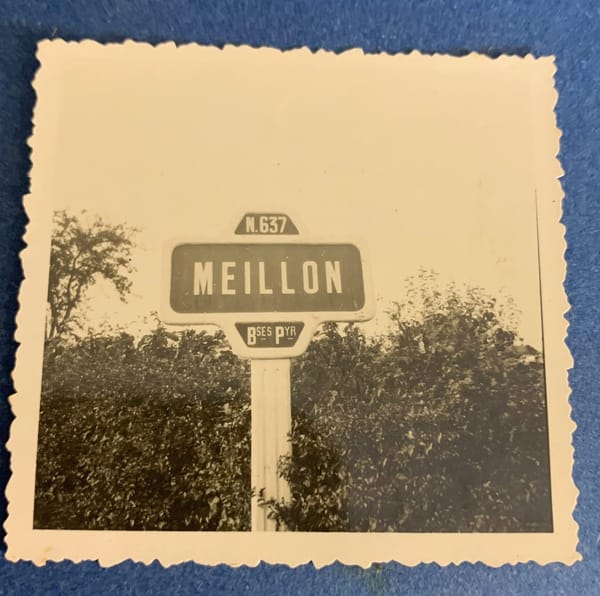

Indeed, growing up, I had been told that at some point, my father’s family had owned a silk factory in the little town where he was born and lived – called Ansbach, in Bavaria, Germany. I also knew that the Nazis had passed laws – the Nuremburg Laws — prohibiting Jews from owning or running businesses, and that my family had signed the factory over to my father’s sister’s husband, a gentile by the name of Reinhold Lutz, whose name she carried as long as she lived, even though they had divorced – again, I was told, in order to comply with the Nuremburg Laws. And, finally, I had been told, after the war, it turned out that the good Dr. Lutz – he had been a dentist until fate had made him the owner of a silk factory – had remarried, fallen in love, had children, and thus could not remarry my aunt as originally planned.

And that, as far as I was concerned, was that. No one suggested the silk factory was still in existence, and it never occurred to me that it would be.

So, family-run, eh?

My physical, intellectual, and emotional journey into the history and fate of the Kupfer silk factory, and of the German-Jewish side of my family, is the principal subject of my memoir. But a dear friend recently upbraided me for writing a memoir that is in many ways just the beginning of the journey, and that doesn’t do the subject entire justice.

This stack is my response: my commitment, every week, to further unpack many of the themes and to unravel the threads that I touch upon in the memoir, and to tug a little more firmly, to yank more forcefully on areas that I might have left a little under-explored in the memoir.

Because the Holocaust is today more than an event; it is a series of crucial lessons — some obvious and some more subtle — that resonate across the chasms of generations and geographies, more powerfully than ever. There was never a “sense” to the Holocaust — the Shoah was an unmitigated and unreasonable disaster — but the lessons we learn can help us and our children into the future.

So think of this less as a memoir than as a history in which the artifacts, subtitles and footnotes are the actual text. It’s 1961 revisting 1941 in 2023.