The Unbearable Ambiguity of Registration

There are some registers where you don't want your name to appear, and others to which you cling for dear life.

In our day, registering has no sinister connotations. You register for an event, for college, summer camp, you register to vote or to volunteer.

But registration can also be ominous. There are some lists you don’t want to be on; some places where you don’t want your name to register. Labor, internment, and death camps fall into this category.

My father had the good fortune of being assigned to an internment camp called Gurs, after a series of powerful storms rendered the camp at St. Cyprien-Plage uninhabitable, even for undesirable aliens such as German Jewish and Belgian refugees.

Gurs was scarcely better. A slip by an elderly person during a nighttime excursion to the latrine would often result in death by drowning, if the unlucky prisoner was unable to lift her face from the oleaginous muck. Rations were small and irregular, and treatment by the guards impersonal at best.

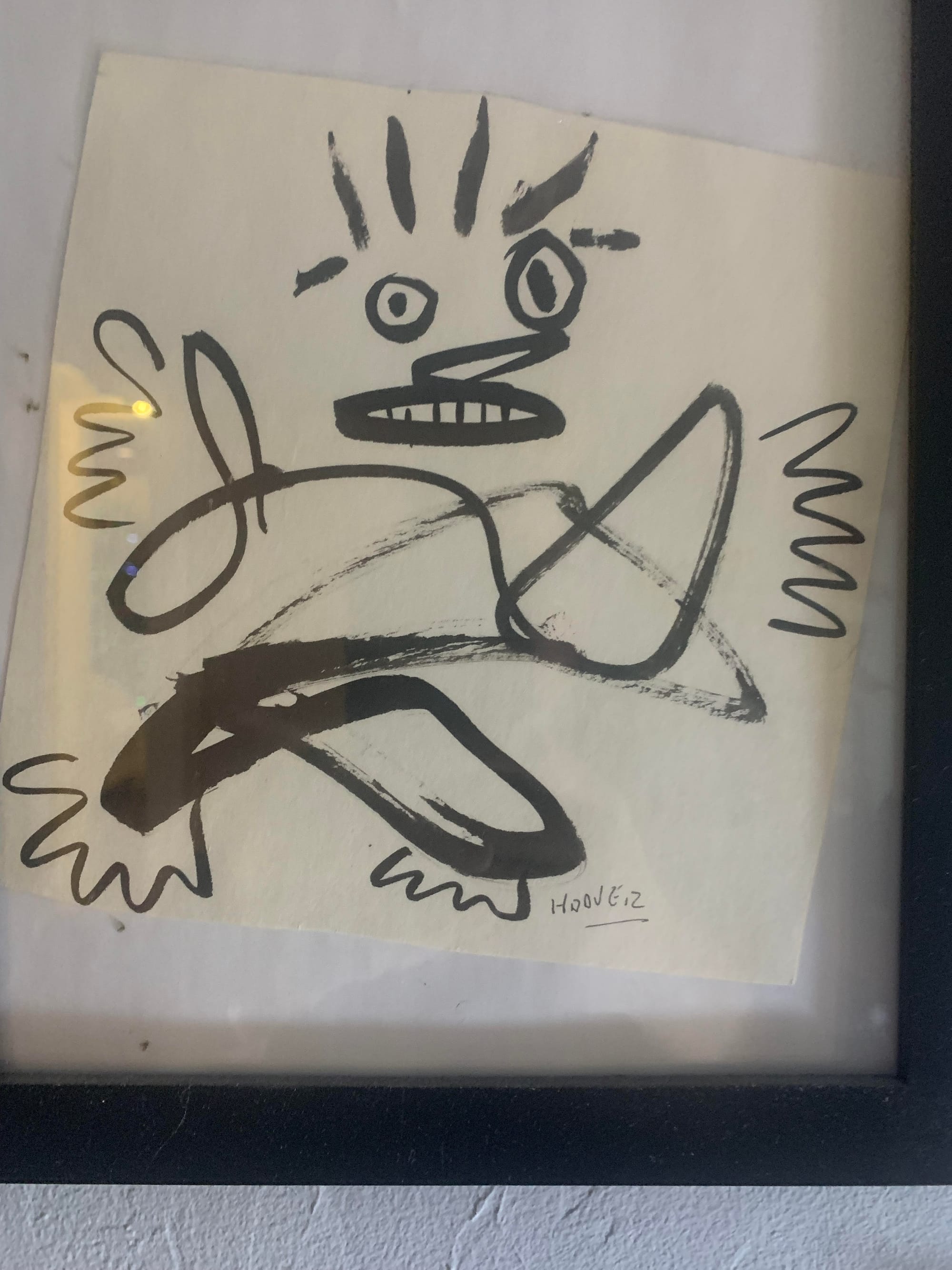

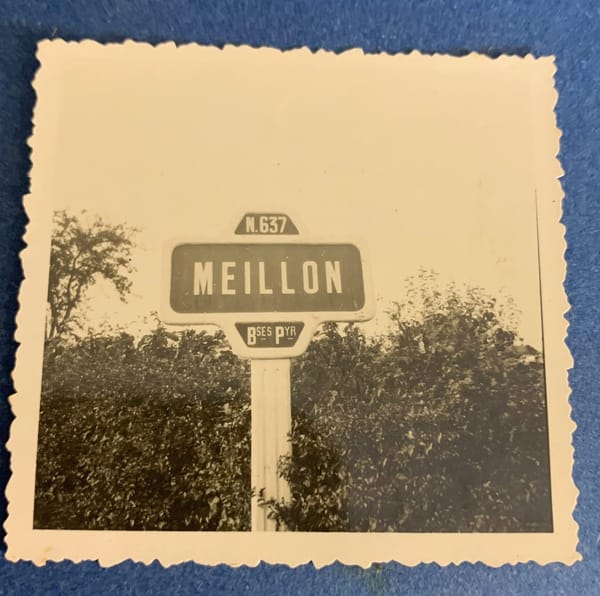

But my father, and thousands of others, were lucky to be assigned to Gurs because it meant they had a possible way out. Some fortunate subset of those tens of thousands who passed through the gates of Gurs were able to live in the nearby town of Meillon, whose extraordinary mayor, Paul Mirat, a former impressionist painter, horse breeder, and farmer, organized his 600-strong fellow residents into a makeshift hostel, an augberge de refugies, if you will.

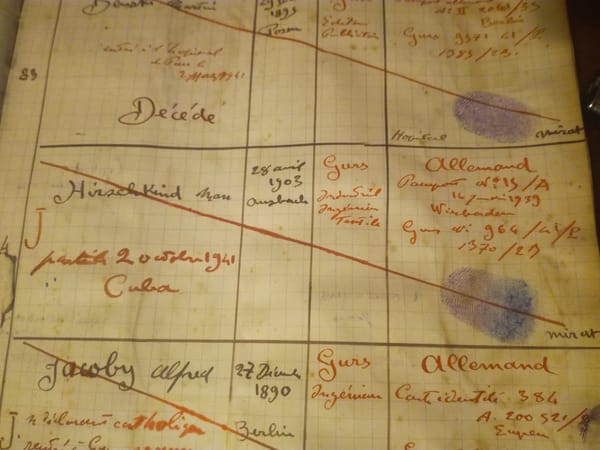

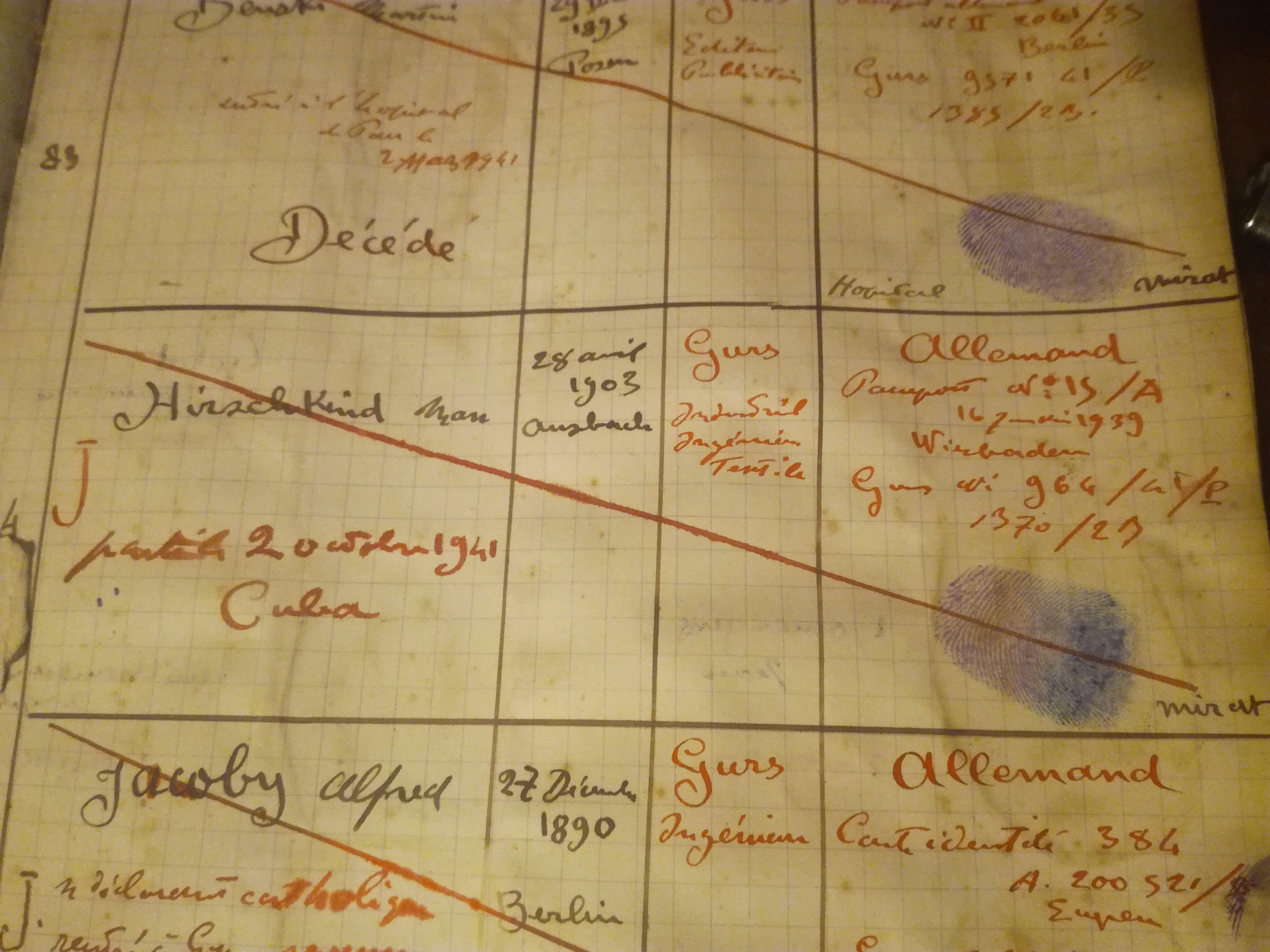

To keep things on the up-and-up, he kept a register of all the people who lived in the town, including those who, like my father, lived in his home or the stables on his property.

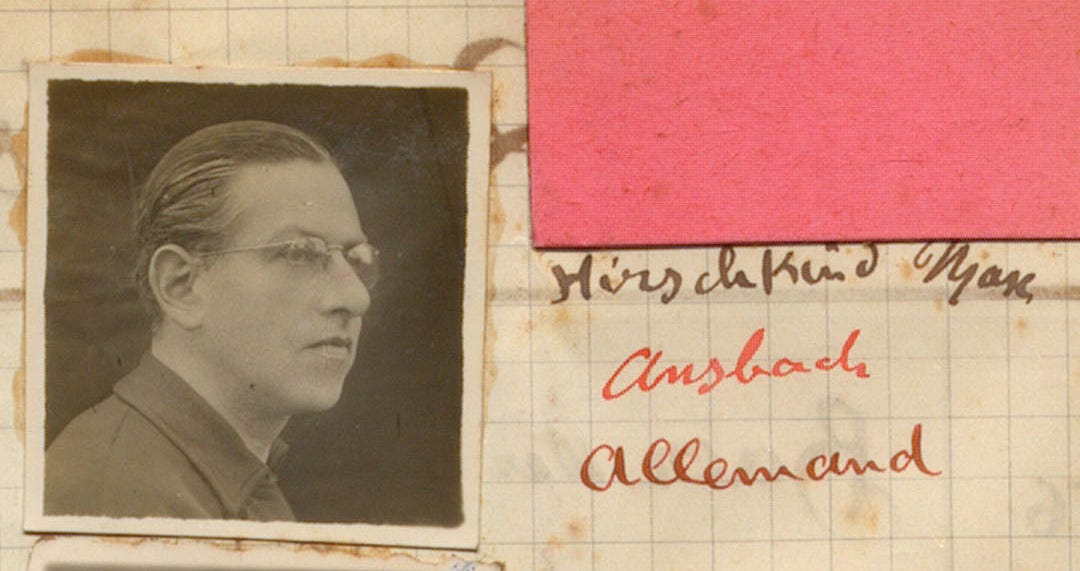

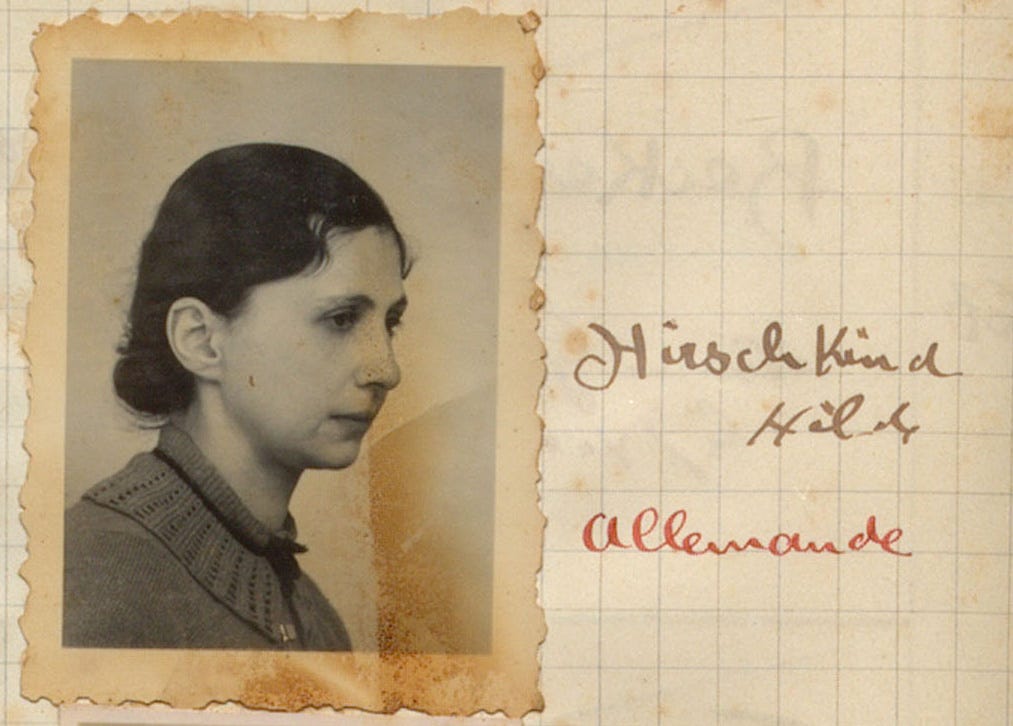

The register, pictured here, included the dates of birth, profession, last place of residence, a fingerprint, where the people were staying, and any linens or other household items they were lent. They also included photos for the purpose of identification.

This register was meant as a means of protecting himself, of course, in the event that the Gestapo should wonder if he were helping Jews escape their clutches. Nothing to see here, he seemed to say; I’m just going along with the war effort or something.

But behind this was a deep-seated desire to help refugees, a long procession of whom he had witnessed since the beginning of the Spanish Civil War (Spain being just on the other side of the mountains). It didn’t matter to him whether they were Jewish or Christian, or Belgian, Spanish, or French. Above all, they were human beings in his eyes, and deserving of kindness.

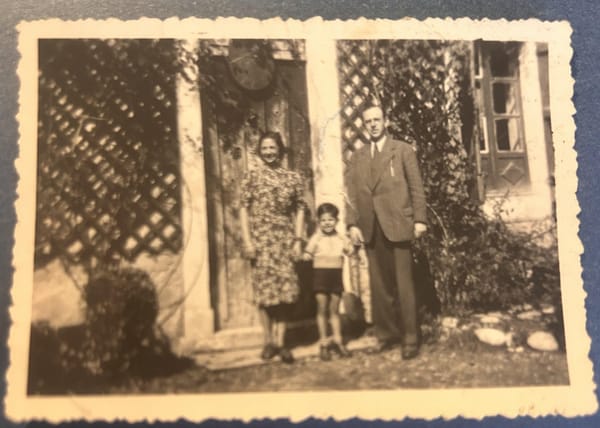

I know this thanks to a couple of photographs of Paul Mirat, taken by my father during his time in Meillon, signed on the back by Paul Mirat “affectionately” and “with friendship” to Max and his then-wife Hilde.

I also know this because when I tracked down Paul Mirat’s grandson, also named Paul Mirat, he showed me the register, which he had kept for all these years without quite realizing its importance. He has since donated it to the official archives.

When he showed me the register, with the names of my father, of Hilde, and of my half-brother Walter, I realized that I had never before seen a photograph of Hilde.

There’s a reason for that – a very sad reason. After they were able to escape to Cuba, my father discovered that she was having an affair with the same man she had been seeing before she married my father.

The story I was told is barely credible – she killed herself by drowning after he refused her a divorce but said they would henceforward sleep separately. There was no doubt that she had killed herself because, I was told, she wouldn’t have had any other to go into the sea, as she hated swimming.

Her demise was officially ruled accidental death by drowning, but the story I was told was that my father prevailed upon the coroner to rule it an accident so as to spare their young son having to know that his mother killed herself.

At one point, we must have had hundreds of photographs of different family members. But none of Hilde, none of my father’s mother Dora, none of his aunt and uncle Lily and Theo (of whom I had never even heard until my recent trip to a Wiesbaden memorial) – as if to say that those who died are gone forever.

Their memories were proscribed because of my father’s implacable anger. He was not someone prone to sudden rages, but if you were dead to him, you were truly dead to him. The register of the dead even included one of my sisters and a brother. As a child, I lived in terror of ending up on that register.

My father died, and I was emancipated; I was free from the fear of ending up on the register of those who were dead to my father.

There are some registers on which you’re happy to appear; others, not so much.