Unity Against Fascism

You don't have to be Jewish or a labor leader (or both) to fight Nazis, because we all have a target on our backs.

During WWII, Jews, union organizers, and leftists had one thing in common, which was having a big fat target on their backs when it came to Fascists.

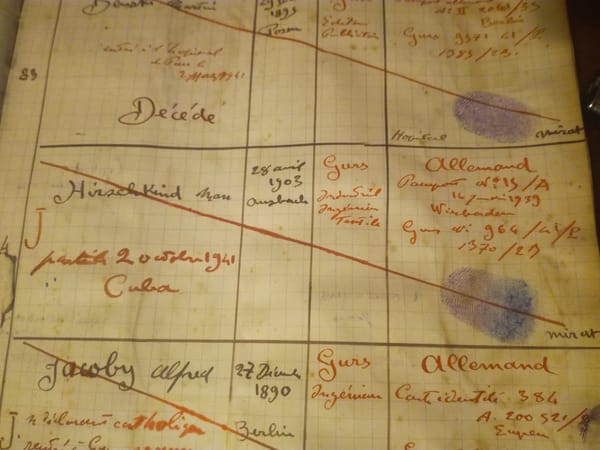

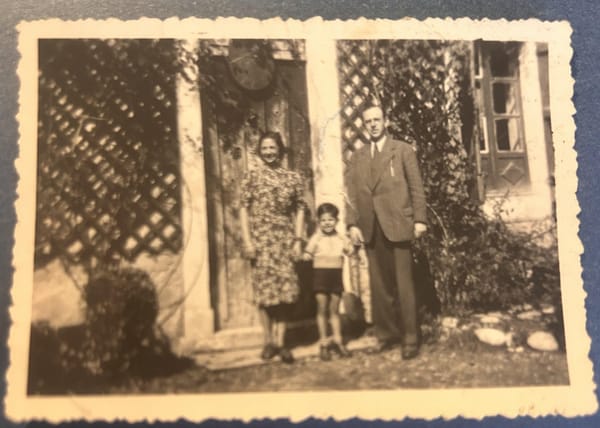

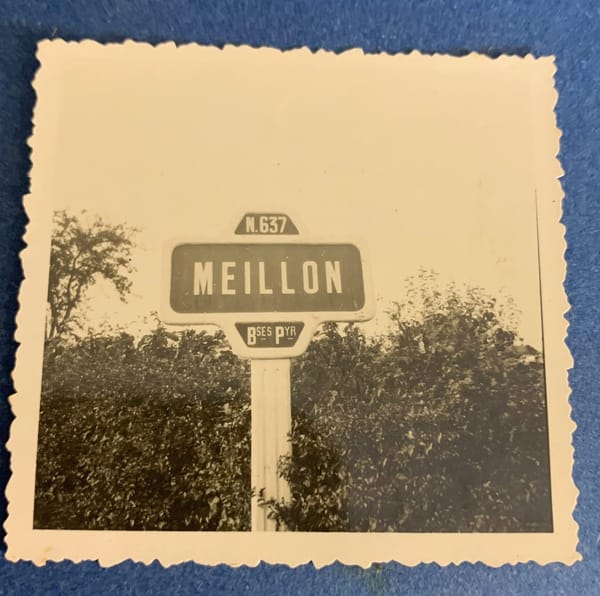

This helps explain, at least superficially, why a Frenchman living in the tiny village of Perpignan, in southwest France, would provide an affidavit stating that he would provide living quarters to a random German Jew, his wife, and their four-year-old son.

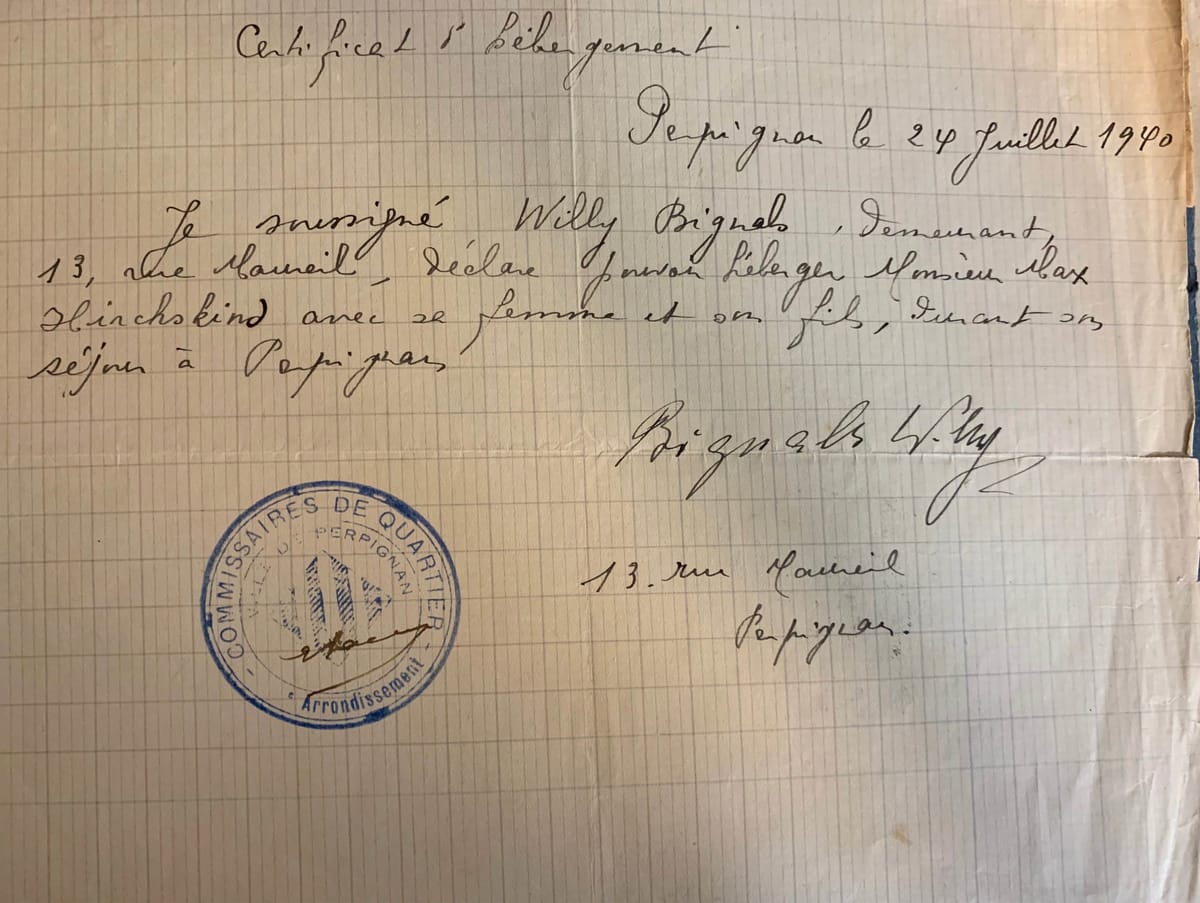

The note at the top of this newsletter reads as follows:

Proof of Accommodation

Perpignan, July 24, 1940

I, the undersigned Willy Bignals, living at 13, rue Maureil, declare that I can provide accommodations for Mr. Max Hirschkind, along with his wife and son, for the time that he is in Perpignan.

Signed, Bignals, Willy

The affidavit is (obviously) handwritten on a sheet of standard quadrille French notebook paper, probably cut from a kid’s notebook.

Bignals was active in the labor movement – I know this thanks to historian Dominique Piolet, who unearthed a newspaper article from the newspaper Le Midi Socialiste, which named Bignals among a list of union organizers who in December 1941 were freed from an internment camp at Nexon, in the Haute-Vienne region of France.

There is another news report from several years earlier showing that Jacques, one of Bignal’s sons, when he was 15, shot and killed his younger brother Fernand, 11, in a hunting accident. This incident, distressing as it must have, didn’t prevent Willy from acting on feelings of empathy with German Jewish refugees in distress.

I don’t want to put too much emphasis on a single anecdote, nor make too much of the link between union activism and acts of compassion. Perhaps it’s enough for me to simply say thank you, Willy Bignals, for having helped my father at a time when he desperately needed a port in a storm.

If you’re wondering why my father was anywhere near Perpignan, it’s because he’d been living in neutral Belgium until Germany invaded that country, and all males 16 and older were deported to internment camps in France. My father was sent to one at St. Cyprien, which is close to Perpignan.

You can read more about this in my memoir, The Silk Factory.

On the other hand, why not extrapolate a little and say that someone willing to go to jail, someone willing to put his life on the line to help his fellows earn a better living, have a pension, medical care, shorter work days and time off, is maybe someone who would also help strangers.

And just maybe, conversely, that kind of activity tends to turn one into someone with more empathy.

Finally, aren’t we all Jews or union activists or gay or something or other that a Fascist might decide is fair game for imprisonment or death? Don’t we all have that target on our backs?

I’m very, very luck to be here. My father was very lucky. People — Paul Mirat, Willy Bignals, and probably many others, had in hand in helping him survive the war and the Holocaust.

This is the sort of history— small acts, personal acts — that reminds us of our common humanity.

PS I’m still figuring out what to do about the Nazi problem on this platform, looking around for alternative publishing platforms. Will advise.