The Forgotten Woman of the Holocaust

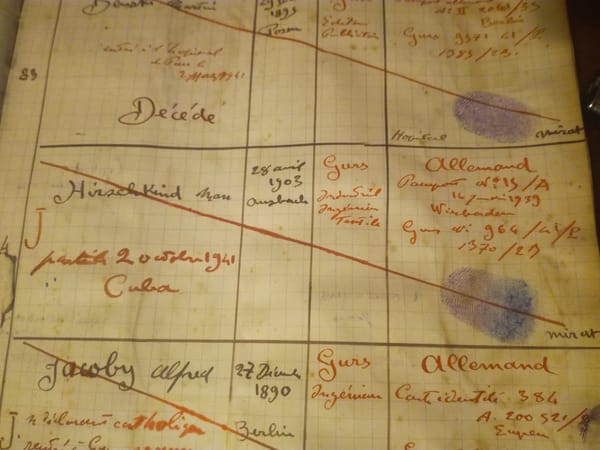

There once was a woman named Hilde Hirschkind née Bomeisl, and she was my brother Walter’s mother. She wasn’t, however, my mother, because she died long before I was born, under circumstances that were shrouded in mystery.

Her face was unknown to me for more than 50 years.

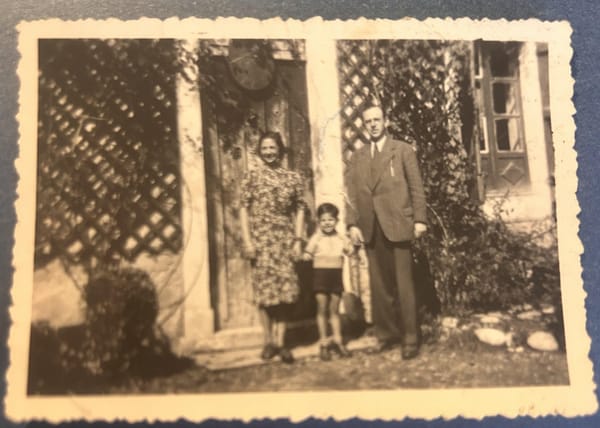

Her expression in this snapshot tells it all: unbearable depression, humiliation, deep anger. She was completely out of her element – in a country where no one spoke her native tongue; while others (including her sister) left Germany, she remained because her husband remained, as did her father. Her father, like her husband, was the owner of a small manufacturing company (toys for Mr. Bomeisl; silk threads for Mr. Hirschkind). She had a comfortable upper-middle class existence filled with high culture and the warm certitude that she was in the best possible place for a Jew in Europe.

While other members of the Hirschkind and Bomeisl families left for England, the US, or Israel, my father and his nuclear family remained on the Continent. They remained in Europe because my father’s mother, Dora Hirschkind, and her sister Lily, remained in Germany, in what they believed to be a Sanctuary City – Wiesbaden.

My father and Hilde eventually found refuge in Belgium, until Nazi Germany violated that country’s neutrality and invaded it in May 1940.

There, my father was arrested along with several thousand other “foreign” males over the age of 16, and sent to an internment camp in France, from where he would almost certainly be deported to a death camp.

Hilde, with their infant son, followed his trail, crossing the battlefields of Belgium and France. She followed him all the way across France to Perpignan, a city close to the Spanish border, and found accommodations close to Saint Cyprien-Plage, the refugee camp where he was taken.

Now she was in a country that considered her an enemy, where her very existence was suspect. Her comfort and ease of mind was no one’s concern. She was the female appendage to my father.

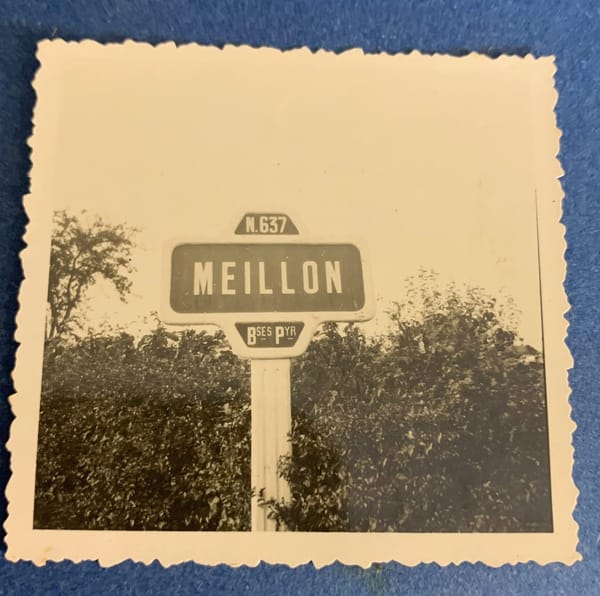

When Saint Cyprien became unlivable, even for refugees, because unusually powerful coastal storms flooded the camps, leading to dysentery and typhoid, Max was transferred to Gurs, another French camp close to the Spanish border, close to the village of Meillon. Hilde followed him there too, all while caring for their tubercular 4-year-old, Walter.

Walter, who tenderly hunted discarded cigarette butts so his father could re-roll the leftover tobacco and have himself a smoke.

Meillon, as those of you who have followed this blog (or have read my award-winning memoir) already know, was a life-raft for many, including my father. The mayor of Meillon, Paul Mirat, had been a painter, a horse breeder, and an agronomist, and he also had a great heart and enormous courage. Mirat convinced that town of 600 souls to take in some 2,000 refugees, most of them Jewish, among whom was my father.

My father was lucky enough to have as his host Mirat himself. Hilde was not so lucky she and Walter were forced by the local magistrate to go back to Gurs.

Then, a little more than a year after his arrest and deportation from Belgium, my father, his wife Hilde, and their son Walter were able to leave France, a visa to Cuba in hand.

Not only was I never told any of this, I had never so much as seen a photograph of Hilde until I traveled to France in 2019, hot on the trail of my family’s Holocaust story (the subject of an award-winning memoir).

Hilde died in Havana, officially the victim of a swimming accident – an anomaly, since she hated the water.

When I was a little older, my mother told that actually, she had killed herself – because, my mother said, my father had caught her in the arms of her former lover from before she and my father married…

That my father had caught them and punished her infidelity by promising her a lifetime of loveless marriage, since he would never grant her a divorce (for the sake of the child). We will remain married but we will never lie together as husband and wife, my mother reported that he told Hilde. (Perhaps it was my mother who would have despaired at hearing such words from her husband.)

That my father prevailed upon the coroner to record her death as an accident in order to spare their son Walter the knowledge that his mother had voluntarily and selfishly abandoned him to this earth.

No one considered that she might have killed herself because of the unbearable news that her father had been killed in the camps.

My father never spoke of her, nor did his sister Beate, who lived in the same Jackson Heights apartment building as us for much of the time that I was growing up. The fact that Hilda had living relatives in the same city we lived in was never mentioned – we knew them, but I had no idea who they were.

When I was still a child, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, my parents would drive us in our white Buick Special to Rugby Road in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn (“abroad,” my father would joke), to visit a couple they didn’t much seem to like but to whom they were attached by an invisible umbilical cord. Lisl Wolf was a very short wrinkled old woman with impeccable red manicures on her gnarled fingers, married to aman named Fred – aka the Gnome -- whose Charlie Brown head was covered by liver spots shaped like Australia.

I assumed they were among the old people they knew from the old country long ago, Jews from Germany who had somehow escaped the clutches of the Nazis. (I now know that many of them left before the turn of the century, while others left in the early 1930s, when the auguries of certain death were unmistakable.)

In fact, Lisl was Hilde’s sister – hence, my brother Walter’s aunt. But no one ever explained that to me. She was just some old lady we used to visit abroad. Even in Brooklyn, she was a victim of the Nazis and the trauma they induced across generations. So much that was unspoken, so much pain, so much betrayal to sort through.

Hilde Hirschkind died in Cuba on May 14, 1944, almost a year to the day (May 21, 1943) after her father, Leopold Bomeisl, owner of a toy factory in Nuremberg, was murdered by the Nazis at the same Sobibor death camp where my father’s mother Dora perished.